Captain Zarathustra, who is the superhero I’ve invented for the sake of this paragraph, is a big-hearted altruist who’s not afraid to take what’s his. By day he moves invisibly among us disguised as a Persian mystic, preaching of good and evil and the cosmic balance between them; by night he preaches nothingness and the Self, gilded and rising above the slurry of humanity around. ‘You could say he’s a man of contradictions’ is the phrase I’ll use when pitching to Time Warner. Also he’s a self-made billionaire industrialist who can solve problems with economic might as well as physical – the full spectrum – though when the situation calls for it he’s not hesitant to unleash his signature move, the ‘eternal recurrence’, wherein he punches his adversary in the face lots of times. His endearing weakness is syphilis.

Captain Zarathustra, or ‘Cap’, as he will be known, depending on the trademarks Marvel holds around Captain America, is, if I’m honest, not hugely original. He’s an individualist with limited respect for government; his superiority to you is innate; he loves personal freedom and societal justice, and is not interested in how one may at times complicate the other; to make an omelette he can and will crack a few eggs, which is to say he is very violent. He is a superhero and he is the dominant mode of our big-money big-audience cultural product of the last 15 years. We pay to see him again and again, and so he represents us.

What I’ve never seen discussed is what exactly this means and whether it can be seen as a mirror of our times in the way that other kinds of film are recognised as reflections of certain eras and their political climates. What I have seen discussed many times, and what is not quite the same question, is whether or not the superhero genre is ‘fascist’, which may be a good place to start.

An article for Salon snappily titled ‘Superheroes are a bunch of fascists’ triggered a round of debate in 2013 when it claimed that ‘Superman triumphs by being able to move faster and hit harder than everyone else: essentially a fascist concept’. Commentators siding with the article rarely stray far from this central claim, while for the most part shooting for the fish-in-a-barrel target of Batman.

If Thomas Nagel’s famous ontological question was ‘What’s it like to be a bat?’ then Batman’s answer is surely ‘Awesome’. His superpowers are money, which he is born into, and the aforementioned physical might, which he exercises beyond the control of any state authority because ultimately he knows what the people need better than they do. An aloof, high-born vigilante, he is an ideal candidate for the F-word. At the pen of Frank Miller he is in addition an arsehole. The Shark Repellent Bat Spray-wielding idiot of yore is, through Miller’s 1986 The Dark Knight Returns, turned into the perfect hyper-individualist of that decade, Pat Bateman without the satire. As China Miéville puts it, ‘let’s not beat about the bush – the underlying idea is that people are sheep, who need strong shepherds. This is a bit fascist – or at the very least unpleasantly Nietzschean.’

Captain Zarathustra nods in approval. But, just at the moment Batman seems to corroborate the idea of a certain politics surrounding the superhero, we see the rest of Miller’s work: Sin City, where violence is an aestheticised end in itself; 300, where some towering Caucasians defend the cradle of Western civilisation against a horde of swarthy, sexually ambiguous foreigners; and the more recent Holy Terror, which is by all accounts intensely Islamophobic. In short, Frank Miller is a man of a certain persuasion and that will come out in what he makes. Perhaps, then, instead of trying work our way from the rooftops of a genre down to the sewers of its politics, it may be more revealing to head straight for the manhole.

It’s been mentioned that many of the claims around superheroes take the assumption that fascism is might, the will made physical. Now, a message from my fondly remembered degree module on fascism is that it’s a slippery concept and arguments around a core definition of what it is, the so-called ‘fascist minimum’, have raged for decades. Few scholars of the field, however, would reduce it to mere brute force. The inclination to do so comes largely from the trickiness in sluicing out an abstract, ‘pure’ fascism from the historical instances in which it has occurred. It’s easy to speak of regimes which are commonly received as fascist and which are also known for their violent methods, but the scholar would here point out that those regimes also wore trousers, and that does not make trousers fascist.

Often implicit in the accusation of fascism is that it’s synonymous with ‘extremely right-wing’, but this is muddled when we consider that the apparatus required to maintain the level of control preferred by fascism would be incommensurate to the diminished scale of government found on the far right. Fascism is anti-state but also, in its acceptance of innate hierarchy, authoritarian, and this poses a problem to those who would try and perch it neatly on the political spectrum. You could say it’s an ideology of contradictions – this is arguably a defining feature of it. Some examples: fascism is both anti-liberal and anti-Marxist; it celebrates the efforts of the individual over others while explaining those efforts through biological difference; it asserts both a return to old values and the clean slate of a new utopia – as cheeky Slovenian Slavoj Zizek puts it:

Fascism is at its most elementary a conservative revolution… a revolution which would nonetheless maintain or even reassert a traditional, hierarchical society… modern, efficient, but at the same time controlled by hierarchic values, with no class or other antagonisms.

In order to ignore class antagonisms, he argues, fascism needs to create a common enemy established along clear and unchanging lines – biological lines are easiest – and this is done by controlling how people define themselves and others. In Umberto Eco’s 14 general properties of fascist ideologies, he labels the property relating to this as ‘Obsession with plot’. To my mind, rather than a cohesive political position, fascism is foremost a practice or method: it is above all about telling stories.

The notion of the ‘foundation myth’ can be seen as an interesting parallel between fascism and superheroes. This type of myth is the story common to fascist discourse wherein a fictional point in the past is explained as the moment when the people emerged as qualitatively different from surrounding groups, this difference serving as justification for recognising that difference in the present. The existence of a superhero begs a foundation story, and each has one: the difference must be satisfyingly explained, and it always is. Similarly, the superhero him/herself functions as such a story to the audience. Being in some way linked to a nation will, despite no overt discussion on the subject of nationhood, serve to substantiate the inherent might of that nation (or any type of group you could mention), this manifesting through whatever powers the superhero has.

So parallels can easily be drawn, even when using a slightly more detailed description of fascism. But do these tally with fascist film and fiction of other genres and are there crossover traits which may help us pin down any ‘inherently fascist’ element of the superhero genre? Unfortunately (or perhaps not) there isn’t much to work with. The original Starship Troopers, a 1959 sci-fi novel by Robert Heinlen, is considered by many a fascist work, with its utopian militarism based on a sacrificial brand of responsibility to the greater good.

The Cthulhu-tastic stories of HP Lovecraft feature grotesques and monsters which are not hard to trace to his racism – ‘a bastard mess of stewing mongrel flesh without intellect, repellent to the eye, nose, and imagination’ could be a line from ‘The Shadow over Innsmouth’ but was written by him about the inhabitants of New York’s Chinatown (the genre of horror owes itself largely to him – and in turn to observations such as these). Many of his letters attest to this xenophobia occupying a place of fascism in his mind (and a strangely jaunty fascism at that: ‘we oppose democracy, if only because it would retard the development of a handsome Nordic breed’), but these more political aspects are less evident in his stories.

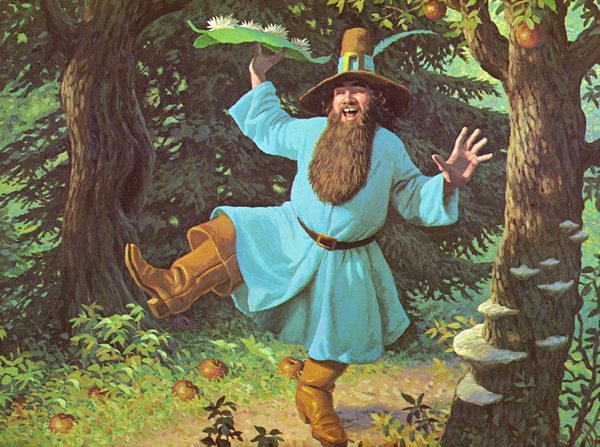

More controversial is the claim of fascism in JRR Tolkien’s Middle-earth, the races of which do bear more than passing parallels to racist caricatures, the orcs, easterlings and southrons, who are spread across its distinctly European geography in a familiar way. It’s been argued that the Shire was derived from Tolkien’s midlands of the 1930s and 40s, reflecting his anxieties during a time of immigrant influx. His letters, or what I’ve seen of them, in no way reveal a man of hobbit-fuelled hatred. Quite the opposite. So the use of racially determined behaviours which reflect real-world stereotypes was either deliberately used and concealed, it was subconscious, or he just thought it was harmless. Many would suppose the latter and agree that it is harmless, that we’re talking about wizards and goblins here and it’s best not to over-think things, but it’s certainly worth noting that The Lord of the Rings is long beloved of fascist groups in Germany and in particular Italy – precisely for its vision of race. Maurizio Gasparri, former telecommunications minister for the neo-fascist Italian Social Movement–National Right party (grandchild to the National Fascist Party of Mussolini), once said ‘Tolkien designed our whole value system’.

None of that explains what the hell is up with Tom Bombadil, but it does appear that among the varying claims of fascism found across The Lord of the Rings, Lovecraft’s stories, and Starship Troopers (as well as among others faced by similar accusations – Salvador Dali, the vorticists and futurists), is a distinct commonality: fantasy. The art of the political right has, it could be argued, a proclivity for other worlds, be they the past from which we should never have moved on or the glorious future we can attain. The world of the superhero is no lefty social realist parable: it is fantasy. One could say that it ticks some of the right-wing boxes (distrust of government or authority beyond the individual; disinterest for situational explanations of behaviour; acceptance of entrenched hierarchy), but a crucial aspect is that, although it is accepting of the inherent differences it sets up between the normal and the ‘super’, it does not imply the need for antagonism as a result of that but rather a will to protect: it’s individualist but not illiberal. The common pattern is right-wing sentiment of a fantasist bent.

There are right-wing films and there are left-wing films, of course, and personally I value the mixture. I like to think that art should reflect how people feel rather than how they ought to feel. But why has this century’s paying audience responded to films of this leaning? A look further back at how certain genres have been associated with historical periods may provide a basis. The classic case is the alien invasion films of the 1950s and their common association with post-war paranoia of invasion from the new enemy, a powerful and inscrutable Soviet Russia of which aliens were a compelling surrogate. Fear of Russian military might was brought famously to life in The War of the Worlds, while fear of the Soviet ideology came in Invasion of the Body Snatchers. In the 1990s emerged a spate of disaster films which played on fears of man-made climate change, melting icecaps and holes in the ozone layer, as well as the coming year 2000 with its sense of change and, for some, catastrophe. Films like, Armageddon, Deep Impact, Volcano, Twister, Titanic, Jurassic Park, Godzilla and many (many) more realised a world which we suddenly saw as bigger and more powerful than us, having been perhaps blinded to this by the incomparable technological progress of the twentieth century. As for the 2000s, or perhaps better ‘the long 2000s’, its Hollywood cashcow is the superhero. Why now?

The alien invasion and disaster films were chiefly about monetising fear. ‘Just so you know,’ they say, ‘this is how you’re going to die,’ and this is apparently something we really enjoy being told. At the beginning of the last decade were the 9/11 attacks and with them a new fear, a new other. The problem this time was that the motivations of this other were so unrelatable, their geopolitical origins so complex (and awkwardly self-inflicted), that there was and has since been remarkably little examination of what those motivations were. ‘Hatred of our way of life’ was deemed sufficient explanation in the autumn of 2001 and has been little expanded on since. As of that time, many films have addressed this new climate of confusion: Steven Spielberg’s 2005 version of The War of the Worlds has been called the first reaction in film to 9/11 and its New York setting was a very conscious invocation of the attacks; 2008’s Cloverfield does the same thing but cleverly withholds the object of fear in order to make it more generalisable. Far beyond those, though, is 2007’s No Country for Old Men, which describes a changing world that is non-fantastical, this time, but just as incomprehensible as aliens or monsters in how its occupants have come to behave, as if humanity itself is changing from some honour-based criminality of the past into something unknown and terrifying (Cormac McCarthy’s original novel and his The Road are often cited as reactions to the post-9/11 climate).

These films make introspective examinations of our own fear and no attempt to move beyond a world divided between good and evil. Films have of course always contained goodies and baddies, and have always been about escapism, to one degree or another, but what I believe has made the superhero film so dominant, and far more numerous and successful than other post-9/11 films, is that it does not merely use good and evil as a dramatic motivator; the inherent nature of its use good and evil, and the ‘origin stories’ used substantiate that nature, amount to an active celebration of this dichotomy, and in this the superhero film is a more powerful escape from the impossible ambiguity of the ‘terrorist’ enemy.

But where they really succeed in capturing the will of the audience is in how they respond to a major aspect of the post-9/11 atmosphere: the sense of having been wounded. Contrary to the likes of Cloverfield and No Country for Old Men, which take the more traditional ‘fear film’ approach of being passive windows on to a world which is changing, becoming irreparably more dangerous, superhero films embrace the yearning for victory brought about by having actually received the first blow (bear in mind that the Russians never invaded, Ben Affleck never exploded in deep space), and they proceed to enact the resulting fantasies of retribution. Their world is clear, its origins and meaning explained, and the goodies will beat the baddies. In times of confusion, triumphalism is highly bankable. Nuance is kryptonite.

The linked Salon article quickly writes off 9/11 as an explanation for their success:

It’s an unfortunate coincidence that the Marvel-led boom in comic-book movies (which had actually already gotten underway before 9/11 with Blade in 1998, X-Men in 2000 and Spider Man filmed in the summer of 2001) – should have coincided with the ‘War on Terror’.

Superhero films have been around for decades, yes, but the number made per year and their box office success is dramatically different pre- and post-2001. This does not of itself imply a causal relationship, but it does point to something triggering a change at that time, and I think the arguments are strong enough for that to be the major geopolitical shifts and national fears of the moment. It wouldn’t be the first time these have sold tickets.

But, as highlighted in the earlier discussion of Miller, it’s one thing to say that a certain genre lends itself more readily to a certain political discourse and another to say that the discourse is inherent to that genre, where any instance of it must necessarily have that same meaning. As convenient as it would be to set concrete laws around these things, a genre, or even a particular story, is not inherently anything. Cloverfield made reference to post-9/11 fear, while the 2010 Monsters used a near identical method to strongly evoke US fears of immigration from Mexico (whether the director intended it or not). Paul Verhoeven’s 1997 film of Starship Troopers is a satire of exactly what Heinlen’s 1959 novel expounds, simply by filming it and seeing it through the cynical lens of the ’90s (some natty SS uniforms helped as well). A great example here is The War of the Worlds, with the 2005 Spielberg version using post-9/11 fear; the 1954 version using the Red Terror; Orson Welles’s infamous 1938 radio version tapping into anxiety over Nazi expansion in Europe; and HG Wells’s original 1898 novel being an allegorical criticism of the behaviour of the British Empire, with Wells noting the extermination of the aboriginal population of Tasmania as a particular inspiration.

That’s a lot of mileage for a story about Martians invading Woking. It’s interesting and perhaps slightly depressing that the most progressive use of the story (where we are the fear) is the oldest. But use is indeed the key. That’s precisely what the story is: its method – and this is separate from what it means, like a tool is separate from what it makes. Certain tools may lend themselves more to certain jobs but that doesn’t mean we should confuse the hammer with the birdhouse. This is central to any debate over the politics of superheroes or over anything else in art: the secret mobility of meaning. For the most part we prefer not to recognise this because it makes things difficult to speak about with the kind of definitiveness that keeps us comfortable. ‘Superheroes are a bunch of fascists!’ is as devoid of nuance as superheroes themselves, but will always be snappier than ‘The shifting collection of tropes we commonly refer to as superheroes is through the lens of our ambiguously fearful time evocative of a certain brand of right-wing politics but not necessarily!’

But are these politics merely reflective or do they propagate? That is, in culture, one of the biggest questions of all – though no time to think about it now as MGM just emailed saying they’re willing to hear my pitch on ‘that syphilis guy’ Zarathustra on the condition that I give him a sassy sidekick. I’m thinking this could be his sister, who would maybe have a sassy habit of misrepresenting everything he says to make him sound anti-Semitic, and later some fascists make him their hero on the basis of his sister’s retelling. The Captain is cool with this, however, as he knows that the fascists can’t pervert his essential nature when neither he nor anything has an essential nature to begin with. This is his laid back side, which I think will play well with the 15–24 demographic.

I’m off to get the artwork sketched out so I’ll leave you with his pluckiest catchphrase:

Man is a rope stretched between the animal and the Superman – a rope over an abyss.

Thanks, Cap!

Featured image by Liam Brazier via www.liambrazier.com