In a world of political ambiguities and blurry-eyed predictions over where this or that path might take us, there is something of which we can be sure: dystopia is bad.

But wait, might one not hold a certain perverse admiration for the logistical trophy of a smoothly run authoritarian superstate? That despot’s nightmare won’t dream itself into being; it requires draughtsmen and model-makers, high-viz surveyors unfolding theodolites on parkland that will soon be bunker-citadel to the Ministry of Feels. Spare a thought for these servants of Oceania, of the World State, of Mega-City One, who (under immense pressure) get their heads down and get the job done. It’s a rare discipline which can maintain political neutrality while the population is forced to slavery, wired into machines, and finally reduced to a nutrient-rich paste.

Typically these professions stay behind the scenes, but it’s their work which forms the literal foundations of the political and social complexities evoked through much of the dystopian genre. Here follows a look at the relationship between those complexities and the imagined locales which give them space to breath, or not, and at how literary advantage is taken of the unloved but enduring assumption beneath all architecture and urban planning: design of the built environment can transform the psychology of the lucky little mites who live in it.

This principle fits equally with utopia, and as we traverse the twentieth century we’ll perhaps glimpse a broader cultural relationship between these two sides of the same speculative coin: utopia as visions inspiring real-world initiatives; dystopia as those initiatives provoking further visions, but now cynical. Together they form a loop of ideas from art to life and back again, one which I will argue makes greater use of the non-rational, the mystical, than is generally known. And this loop of course means that dystopia, hip though it is, exists only as antithesis to its uncool cousin, therefore any analysis must invite both to the party. Even if utopia brings its weird friends.

Gardener’s world

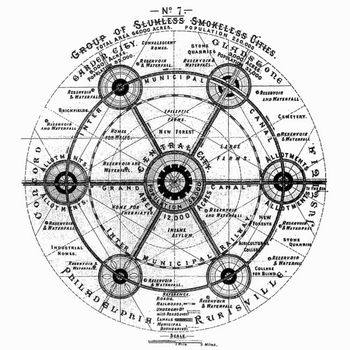

It has brought its weird friends. The first is Ebenezer Howard, who in 1902 published Garden Cities of Tomorrow, a book propped by some of the major pillars of Victorian thought: radical reformism, sky’s-the-limit industrialism and an awakening environmental tendency. It proposed a network of entirely new cities, planned to delicate wheel-like designs around green space. In the garden city, all amenities would be provided and ownership based on a free-hold model where citizens own the land together as a cooperative from which they individually lease their plots. Self-governance and self-sufficiency is key, with minimal state assistance and private backers brought in through an air-tight business case.

This was unlike the craft-based medieval socialism of Nowhere, William Morris’s earlier ideal society. Howard downplayed socialism as a label, instead picking a route between the collective and individual wills, which he saw as a tension in human nature to be calmed and unified through large-scale planning. His peaceful bottom-up change would be a reconciliation of the opposing urban and rural forces, rather than revolution and the wounds that come with it.

He made this pragmatism key to his pitch for the garden city movement, doubtless aware that it would be the safest tack with investors, though to the contemporary eye his model could be seen perhaps as a form of anarchism. He was certainly aware of arch anarchist Peter Krotopkin just as he was aware of Morris and John Ruskin. What we now call sci-fi novels were also part of his unusual mix of influences, particularly the works of HG Wells, and Edward Bellamy’s 1888 Looking Backward, about a time traveller who visits a future socialist utopia in America which is adapted with local libertarian flavours.

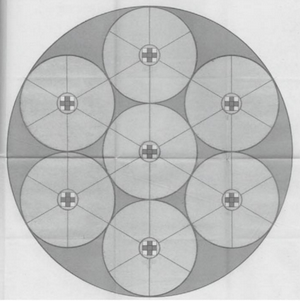

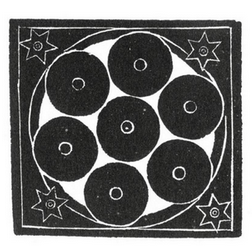

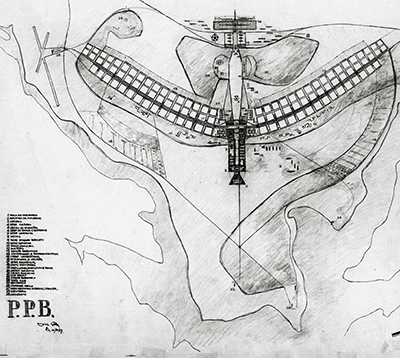

With his love of nature and social reform was another pillar of Victorian thought: spiritualism, with which curious dots can be joined across his work, not least over his famed garden city map. This image (which he claimed was delivered to him as a prophecy from a trance medium he met in Chicago) bears a striking resemblance to the ‘Plan of a Heptopolis’ image from the esoteric work Palingenesia – dictated, according to its ‘transcriber’ Gideon Ouseley, by spirits. Howard conceded the similarity in a quiet footnote. The image also appears as an engraving which accompanies the monk Giordano Bruno’s 1591 ‘On the Threefold Minimum and Measure’, a poem rich in Pope-troubling symbolism (as well as a pretty much on-the-money description of subatomic matter).

Howard’s image can be seen too in another mystic’s engravings – William Blake’s, alongside the poem ‘Milton’. Garden Cities of Tomorrow opens with the famous lines from Blake’s preface to ‘Milton’, the poem ‘And did those feet in ancient time’:

I will not cease from mental fightNor shall my sword sleep in my hand

Till we have built Jerusalem

In England’s green and pleasant land

Howard’s quotation in fact replaces ‘fight’ with ‘strife’, which scholar Paul Emmons claims to be deliberate and part of a known esoteric tactic for smuggling messages through a text. The entire schema of the garden city, Emmons argues, is just such a smuggling, realising ancient patterns and passing them into popular consciousness in a palatable way, all as a grand bid for humanity to commune with the spirits, build the New Jerusalem and ascend to a presumably engraving-filled heaven.

All a bit odd, but tactics like this were standard practice to figures known to Howard – Blake and Bruno certainly used them – and his spiritualism1A story goes that, at a séance towards the end of his life and after Garden Cities of Tomorrow had become enormously influential, the ghost of Howard’s wife arose, telling him, ‘You have accomplished more than you know’. He was disappointed that she had not been more specific. and awareness of these methods is not in doubt. Whether his suburban planning was a mystical plot or not, the influence of millennial Christianity and of the notion of a New Jerusalem were at least thematically involved in Howard’s work and in the broader utopian thought of his predecessors. In Victorian England in particular, Blake’s ‘Milton’, with its re-imagining of the old myth of Jesus coming to England and wandering around Stonehenge, was seen in decidedly non-satirical terms by many. It became a powerful idea.2It’s possible that England will at some point adopt ‘Jerusalem’, a musical rendering of ‘And did those feet in ancient time’, as its national anthem. Through today’s calmer secular reading of the piece, it would if selected illustrate beautifully the English embrace of myth and nonsense – and our hyper-dissonant love of both stoic honour and self-flagellating satire.

Paradise lost

The dynamism of the early twentieth century was palpable across many spheres. The European mainland was gripped by the slash-and-burn totalitarianism of the futurists while in Britain the vorticists waged war against the entire edifice of Victorian culture, largely with typography, before an actual war happened and the smirking all-caps manifestos suddenly seemed less incendiary. A keen example of how the first world war dismembered the optimism of the arts is in vorticist Jacob Epstein’s 1913 sculpture ‘The Rock Drill’, which pre-war was powerful and phallic, pure sci-fi, then, as Passchendaele and the Somme churned and it became clear as to what this new mechanised dynamism actually meant, Epstein castrated and hew apart the sculpture to leave a new piece with a new meaning, a mockery of its former aggression and naivety. Pessimism had been cut into art.

In post-war Berlin, the local dadaist faction decided they could no longer ignore politics and produced manifestos for conciliation and peaceful reconstruction. One of their demands seems rather familiar…

3) The immediate expropriation of property (socialisation) and the communal feeding of all; further, the erection of cities of light, gardens which will belong to society as a whole and prepare man for a state of freedom.

It’s a curious endorsement of the garden city to have it rubber-stamped by the political arm of an avowedly non-political (and absurdist) movement, but one can imagine Howard enjoying the sentiment.3If not that of a following demand, ‘a large-scale dadaist propaganda campaign with 150 circuses for the enlightenment of the proletariat’ – a scale of elephant-based authoritarianism probably not seen since Hannibal invaded Europe. These artists were looking to rebuild, but others were examining the scars which now crisscrossed society, the new technologies and scales so admired in futurism becoming mixed with anxieties over where people would fit into mass industrialisation and urbanisation.

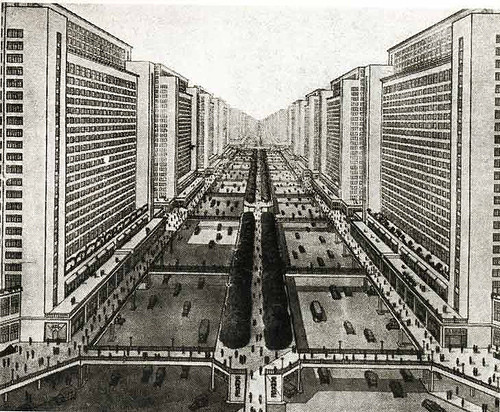

Fritz Lang’s influential 1927 film Metropolis featured a grand modernist city with a huge head-like bastion at its centre called the Tower of Babel, built in image of that in the Biblical story, wherein a tower so large is constructed that it becomes an affront to God and humanity is punished. This story, which was derived probably from a ziggurat built by Nebuchadnezzar in Babylon, is perhaps the most central motif of architectural science fiction.

In New York, architect Hugh Ferriss was using similar imagined mega-structures to produce the maximalist illustrations collected in his 1929 book The Metropolis of Tomorrow. They are not literal designs but rather meant to be taken as a sort of metaphorical future of architecture. Eerily backlit, there is nonetheless no cynicism in the buildings they portray, and little sense of the humanity which they are supposed to be for. But one might forgive this in the context of 1920s New York, which must already have looked like nowhere on earth. The drawings do have their chiaroscuro darkness, but this was part of their awe rather than some political inflection. Their buildings are presumed the work of private capital, tycoons. It’s hard not to think of Gotham City while viewing them.The punishment of the dwellers of Metropolis, however, is reserved for the slavish subterranean workers who get daily chomped in the city’s incinerators, as if sacrifices to the splendours of above. ‘Moloch!’ screams the title card, invoking the Assyrian god Moloch, an enduring symbol of fiery sacrifice. Lang’s Babel is therefore layered with both a greater exploration of the mythic milieu of the Babel story and infused craftily with the politics of 1920s Europe.

Le Corbusier’s phonebook

By the late 1920s there was emerging the forceful talent of Swiss-born architect Le Corbusier. Regarded often as the twentieth century’s greatest architect, and certainly its most prominent, he is worshipped as a visionary who made the social a direct part of his architecture, a society-builder who believed utterly in buildings’ power to influence the minds of those in them; he is reviled equally as a meddler, a blind social engineer, and a man who could not separate his work from his dubious politics.

Villa Savoye, perhaps his most famous building, demonstrates these two views. It used revolutionary techniques and was regarded as a masterwork of geometric form, the apotheosis of Le Corbusier’s idea that a house should be ‘a machine to live in’. He believed that it had the power to heal. The house’s owner, though, claimed it was so poorly designed that it had made her son seriously ill, and she sued Le Corbusier.

Undeterred, he continued promoting his visions, hungering for buildings of ever grander social scale, ever more complex machinery for living – architecture so big that it became urban planning. He had designed an angular futuristic city, Ville Radiuse, and proposed a development of Paris which would have entailed flattening more or less the entire centre of the city.

Now in the 1930s, America’s premiere architect Frank Lloyd Wright designed a distinctly oppositional vision to the conformist urbanisation of Ville Radiuse in his own Broadacre City, a design drawn perhaps from the garden city ideal to build on America’s emerging vision of sprawling suburbia. In Broadacre City, nature and cars would work in harmony, all would own land and greenery, and civic infrastructure would be cut to a minimum. Sounding like a vision from Looking Backward, this was an attempt to reconcile mass planning with individualism.

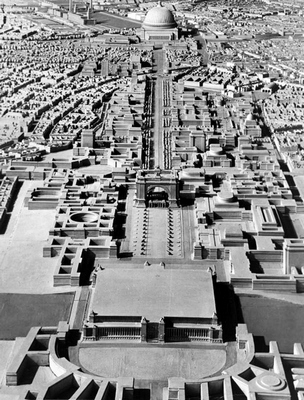

But no such reconciliations were needed for Le Corbusier, who in the late ’30s was courting Mussolini over ultimately unrealised projects in Rome and Addis Ababa. Le Corbusier is considered by many to have been a fascist, and affiliations like this don’t do him any favours, but it’s worth noting that he also worked feverishly to design projects for Stalin (one of which predictably involved the levelling of central Moscow). Potentially his biggest concern was getting his designs commissioned, and that was most likely to come from autocrats of both the right and left. Undoubtedly his focus on technical purity lent itself to the clean-slate politics of these regimes, but an interesting irony is that Nazi Germany and Soviet Russia largely rejected Le Corbusier in favour of neo-classical designs – dictators often having a thing for ancient Rome – yet the one to embrace modernism was Mussolini, whose capital was… Rome.

While baulking at its classical pretensions, Le Corbusier would have admired the comic gigantism of Hitler’s eventual design for a remodelled Berlin, ‘Germania’, of which the planned People’s Hall would have made the Reichstag look like a garden shed. Forced labour from the concentration camps was set to build it in what now looks like an aspirational reconstruction of Metropolis.4Hitler had actually seen Metropolis, afterwards declaring Lang to be the ‘the man who will give us the national socialist film’, so the comparison is not so flippant. Propaganda minister Joseph Goebbels then summoned Lang and told the director he was to take over production of all film in Germany. Lang promptly fled the country. It is curious, though, to imagine Goebbels and the Fuhrer watching a movie together. History is silent on whether they shared a blanket. But work on Germania never started as it was determined that the buildings were so massive they would sink.

Fantastical though many of these plans were, there inevitably came the association between them and the carnage of the 1940s, and this gave a toxic dimension to large-scale urban planning which has never entirely gone away. But these plans also describe another association: between design and art. All of these thinkers understood the power of symbols, from Ebenezer Howard and his potentially esoteric spiritualism to Le Corbusier who incorporated aspects of the human body into his geometric designs, and even to Hitler, whose manipulation of symbols, via the propaganda of Goebbels and the occult interests of Himmler, was key to his power.

Brutal Britain

Once again, utopian appetites found themselves dampened by a world war, and once again dystopian readings slipped in to hold up a carnival mirror to recent zealotry. The major post-war dystopian work, and for many synonymous with the idea of dystopia, is George Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four. In it Orwell addresses the ideologies of the period, its Ministry of Truth forming a physical manifestation of the psychological constraints put on a population during totalitarian rule. For its look, Orwell based the Ministry of Truth on London’s Senate House, the tiered art deco styling of which makes it look like a miniaturised (though still massive) version of one of Hugh Ferriss’s illustrations. A now recurring theme, the political ambiguity of these visions, is present in Orwell’s novel: left-wing readers sometimes presume it a critique of the right, while right-wing readers see it as a critique of the left – more accurately, but often without awareness that Orwell was himself left-leaning, and what that means of the critique5But, where ambiguity is usually a means for an artist to deliver nuance and so create a richer and more reflective work, Nineteen Eighty-Four’s is an ambiguity that triggers little debate or reflection between the two sets of readers. Orwell’s target is of course totalitarianism, but without any effort to disentangle this from one or the other side of the political spectrum (or ideally from both), the story is generally reduced to a tool for contrasting parties to affirm their own beliefs. So, without wishing to blaspheme, I’d say its success as a political commentary is not so certain..

A warning against idealism of any extreme, the novel draws from Britain’s long-standing sense of being apart from the brawling ideologues of the mainland, a spectator overlooking the mess and wanting none of it. This aversion to idealism becomes an idealism of its own, of course, and one that we British are loathe to identify in ourselves. For instance, the massive construction projects required after the war drew from the garden city ideal of entirely new conurbations, but the idealism was watered down into the normal-feeling but still planned-out ‘new towns’. These continued the national pastime of rejecting modernism – architecturally speaking – for its authoritarian associations, and maintaining the pretence of being ideology-free, jackboots firmly on the ground. But still there was a streak of the Arcadian in the new town, a headstrong romanticism which struck a decidedly non-realist British chord.

In cities, things were different. Modernism found an acceptable face in brutalism, a form lacking any kind of optimism (perhaps this was always our contention), with moral seriousness and an unmistakable militarism – but defensive in nature. An irony of this form and Britain’s fussiness over what it borrows from Europe, for fear of any totalitarian baggage, is that brutalism, with its blocky layering and raw concrete planes, seems so strongly indebted to the bunkers of Hitler’s Atlantic Wall. Yet there is a wilful vulnerability to brutalism, with the building’s inner ducts and services often exposed on the outside. The Barbican Estate and National Theatre are its icons, along with the Trellick and Balfron towers of its champion, Hungarian architect Erno Goldfinger.

But the many commissions gained by Goldfinger over the 1960s did not mean that the population was accepting of the style, and he was vilified in the press.6Ian Fleming’s baddy Auric Goldfinger, who liked gold a lot (nice one, Ian), was named after the architect following his bulldozing of several Hampstead houses known to Fleming in order to make way for his own. This villainous naming fed neatly into the public animosity towards the real Goldfinger, who sued Fleming on the grounds of anti-Semitism. The following settlement included six free copies of Goldfinger for Erno. Although beleaguered, Goldfinger was a forceful personality with ideals traceable directly to Le Corbusier, believing that buildings were capable of teaching their inhabitants to live in a better way. In the post-war decades these ideas had risen from the drawing boards of architects and into public consciousness.

Space is the place

Meanwhile, away from the war’s architectural hangover, a utopian project was growing unabated in South America under a very different set of cultural forces. The new and economically named capital of Brazil, Brasilia, had been designed in the late ’50s by two Brazilian acolytes of Le Corbusier (who they had seen deliver seminars on his 1930 visit to Rio de Janeiro – proposing, since he was there anyway, an obliterative redevelopment of the city). The meeting of aesthetics and politics made an ideal setting for the construction of a new capital, highly planned and hyper-modern, and it was completed in 1960. An unexpected upshot, however, was that Brasilia’s sleek space-age architecture, in a wider context of nationalist fervour fused with Christian and folk traditions, gave rise to a space in which numerous sects and cults appeared. Several of these focus on the sacred qualities of UFOs.

The Temple of Good Will is based in a pyramid in Brasilia and incorporates all major faiths. The pyramid is topped with a giant crystal, possibly the world’s largest, which sits directly above the centre of a labyrinth on the temple floor which – just like labyrinths on church floors in France and the pagan labyrinths before them – is traversed as a form of purifying pilgrimage. The Arcadia Institute is another self-help mishmash, this time centred around the construction of a village which is also a dock for the spaceships set to pick followers up before the coming end of the world. The Valley of the Dawn is a large outfit again based around spaceships, these ones hovering in a silent fleet near their compound outside Brasilia. Followers combine Catholic, indigenous, West African and ancient Egyptian beliefs, and dress accordingly.

Of course, any link proposed between this regional proclivity for sci-fi religion and the design of Brasilia will be broad and nebulous, but it’s perhaps not over-fanciful to see something causal in specifically these groups arising in specifically this place, where they are either directly among and drawing from its architecture (via a massive crystal), or overlooking from generally impoverished outlying districts towards the glittering futurist centre of Brasilia, in turn building spaceports of their own.

This should be seen in the wider context of an emerging modernist tradition which was distinctly Brazilian in character, ignoring the more individualist and romantic modernism which Spanish-speaking Latin America had adapted from France. Brazilian modernism, as scholar Stephen Tapscott puts it, ‘built on models of Italian Futurism; it experimented in local and regional idiolects… was outspokenly nationalistic; it was often democratic and demotic’. The curved white planes of Brasilia, sleek and congressional yet embracing of parochial faiths, make more sense in light of this.

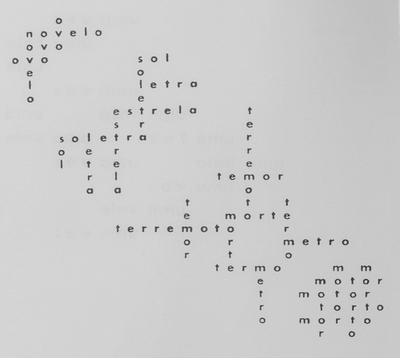

Illuminated too is Brazil’s experimental ‘concrete poetry’ tradition, which was in full swing as Brasilia was being designed. While the graphical arrangement of poetic text was by no means new, it was the concrete poets who saw in this flexible and egalitarian material a symbol of the regenerative and politically welcoming society they wanted. Their visual and structural method helped develop an architecture of words where meaning is built and rebuilt with letters shunted and stacked like breezeblocks. This poetry was, like the buildings of Brasilia, about form and play but with a serious political foundation.

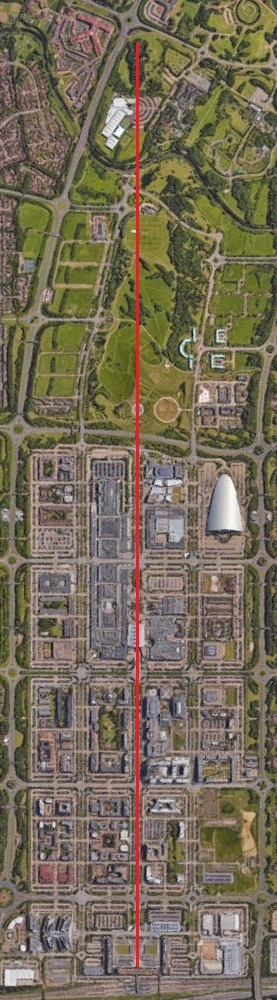

Toying with words was a common tactic for postcolonial cultures to break down the instruments of the former power and make them their own, as was the conscious looking to pre-colonial folk traditions and symbols. The layout of central Brasilia is two sweeping boulevards which from the sky resemble a plane or bird; this makes for a modern iteration of an ancient practice seen across South America.

Machu Picchu, for instance, is alleged to have been planned to create, from a certain vantage point, the shape of a Condor, a bird sacred to the Incas who built it. A thousand years before, the Nazca were making lines on the desert floor to demonstrate images of unearthly creatures and designs of startling geometric precision – at huge scales – to the gods. Over in the Amazon basin, deforestation reveals more and more such geoglyphs, spiritual centres designed to communicate with the skies in a way which makes modern Brasilia, and the cults gazing at it, feel very old indeed.

Philosopher kings

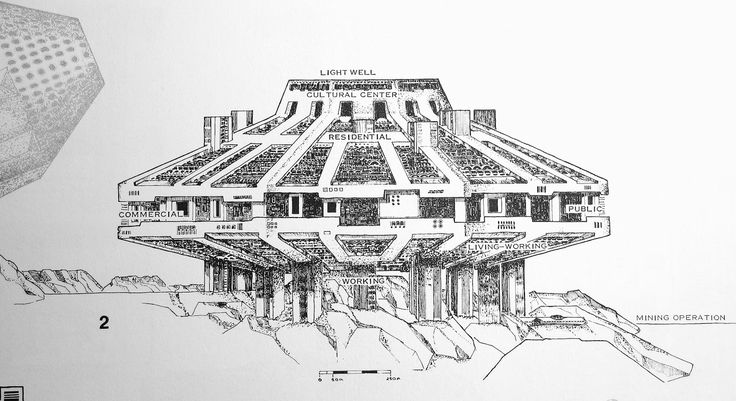

In 1969 the Italian architect Paulo Soleri, working in the US having studied under Frank Lloyd Wright, published Arcology: The City in the Image of Man. His ideas concerned densely populated mega-structures which were pedestrian, efficient, and – most importantly – ecologically harmonious with the surrounding environment. The burgeoning ecological movement of the time fused in his work with the science fiction of Jules Verne and the philosophy of Jesuit priest Pierre Teilhard de Chardin, who believed humanity to be on the verge of a new phase of consciousness through ever greater incorporation and cognitive development. Soleri saw his structures as the necessary physical points at which this new humanity-wide consciousness could appear.

Arcologies are underpinned by a Christian cosmogony but Soleri’s hive-like yet graceful designs (enormously influential to futurologists and science fiction alike) appeal more to sociology and biology, ordered around technologies like hydroponics and wind turbines. In this they were decades ahead of their time, even if their proposed density was at odds with prevailing tastes, especially in the US. Despite this, Arcosanti, an arcology founded by Solari in 1970 in Arizona, endures and grows steadily.

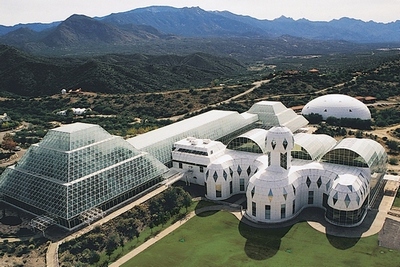

Speaking of quasi-spiritual architectural communes in New Mexico, the Synergia ranch was established in 1969 following the development by architect Buckminster Fuller of the geodesic dome, a latticed structure of triangular tiles where the connections between them are individually weak but together form a remarkably strong structure. Outlined in his book, Operating Manual for Spaceship Earth, Fuller saw the principle of this structure as transcending architecture, becoming a plan for the ideal society where individuals are connections which are without hierarchy and form an organism of unified strength.

This was mana for the day’s countercultural strays, who set up Synergia as a way of realising Fuller’s ideas, even constructing the site out of geodesic domes. The commune continued in various states until its leader – though of course it had no leaders (except its leader John Allen) – used a millionaire backer to construct ‘Biosphere 2’ in Arizona, a series of elaborate geodesic structures designed to hold sealed climates and ecosystems such as savannah, rainforest and even coral reef. In 1991, eight volunteers were were shut inside for two years in an attempt to establish a model for colonising Mars.

The scientific validity of this, though, was troubled by the fact that it was run by a cult. Beyond the consultants brought in from illustrious institutions, there were almost no real scientists on the staff or among the volunteers. The management was all old hands from the Synergia ranch with several being actors in what was called the Theatre of all Possibilities, a troupe run by Allen, based at the ranch and with a chequered past in terms of cult-like practices such as mental and physical abuse. Reports had long circulated of the same practices occurring at Synergia, where the strictly non-hierarchical social structure had equally removed all mechanisms to counteract any naturally dominant personalities in the group, resulting in a sort of fiefdom for Allen which extended to Biosphere 2.7Scattered and criminally unexplored accounts claim that the troupe performed psychedelic plays in the darkness beyond the Biosphere 2 experiment, worshipping totems and even receiving a visit from acid evangelist Timothy Leary. It’s true that Leary visited, and that Allen also knew William Burroughs, who recommended the inclusion of the hallucinatory/cute galago among the species to go inside – and which bred successfully while the pollinating insects and other actually useful species died out. Even Marlon Brando paid a visit, allegedly (and this is Reddit Allegedly, though he certainly did visit the facility) donating a cache of assault rifles. Suspicions emerged of the project being led by ulterior beliefs, New Age apocalytism and psychedelic-induced mystical (and theatrical) rites all under the allegedly violent stewardship of Allen, using science as a shroud for the television crews.

But for our purposes this story is not about the obscure and fascinating personae of Allen, but of the complex reach of Fuller’s architectural ideas. Architects like Fuller and Soleri marked a distinct breed of designer-prophet, a figure which emerged so readily in the cultural conditions of the United States, that petri dish for the messianic and apocalyptic8To which the 1970s environmental movement, so central to Soleri and others like Jaque Fresco, was of course connected, based as it was on a then-new notion of man-made ecological catastrophe.. This figure powerfully encompassed the opposing yet incessantly blending aspects of how architecture was always presumed to relate to psychology: straight, ‘rational’ design; and the supernatural. This latter aspect would not die, not even among the century’s most gifted designers – indeed it seems to have been actively preserved by them.

Back in Britain, and in this climate of the increased intellectualisation of architecture, sociologist Maurice Broady decided to coin a phrase.

Architectural determinism

In his 1966 article, ‘Social theory in architectural design’, Broady claims that the architects and planners of the day had succumb to a nonsense he called architectural determinism, the assumption of which, that design can determine behaviour and sentiment, is no more than ‘speculation masquerading as sociological truth’. He concedes that there is a relationship between design and behaviour, but he makes a distinction between design as influence (being a small factor among many, and which he accepts), and design as determinant (the single overriding cause, which he does not). He thought this assumed determinism not only lazy, because it allays the responsibility of understanding other factors, but deludedly self-aggrandising.

The physicist is apt to suppose that the world could be run much better if only scientists were in charge; the psychologist, that the assumptions about rat behaviour that are helpful in the lab are equally valid as general principles of human conduct. By the same token, the designer may easily come to believe that his work will achieve the social objectives which not only his client, but he himself, wishes to promote.

In a world of Corbusians running amok, Broady’s view was a necessary calming of things. But just as he said, rightfully, that architecture was lacking a certain sociological rigour, so too his sociology is without the philosophical rigour needed to make a go of defining his terms. The problem is in assuming such a neat distinction between ‘influence’ and ‘determinant’, with the former for him characterised by the retaining of a degree of agency (the capacity to act independently, freely) and the latter by an absence of agency. This sounds nice enough, but to really grasp it clearly would be to have an understanding of the colossally complex range of factors which knit together into an individual’s ’caused’ psychological state.9Note that ‘philosophical rigour’ would not be to gain that understanding (although that would be lovely so by all means have a crack); it would rather be to grasp the nature of our lack of that understanding. This is the classic philosopher’s get-out. It’s also utterly necessary. A philosopher would in addition point out that Broady’s is a typical ‘soft determinism’ argument, and like all such arguments it has the advantage of being probably the most measured and practical way to proceed, and the disadvantage of being, on rawly conceptual terms, a mess. It’s those who can’t live with this middle-ground mess who head, as we’ve seen from utopia’s various political manifestations, for the purity of extremism. In other words, determinism cannot be proved, but neither can it be disproved, so it endures in our minds as a means of organising the world around us.

This manner of thinking has a comforting sort of folksy vagueness with which we are long acquainted; what we’re taking about is in effect the same ‘invisible’ forces described by feng shui, which is concerned with the belief not just in the mental effects of how furniture is arranged but historically has played into planning decisions around buildings and even rail infrastructure. Vastu shastra, too, the Hindu ‘science of architecture’, has informed the construction of buildings for thousands of years. Where today we are inclined to describe the relationship between structure and mind with the language of psychology, in the past it would have been the language of mysticism.

But suggesting that architectural determinism has a basis in magical thinking is not quite to claim it false. Consider that in feng shui it is thought inadvisable to live beside railway tracks because they cause chaotic and disharmonious energies; more generally, people don’t like living near railway tracks because they are loud and therefore uncomfortable. Identical conclusions from sentiments of little practical difference– after all, what is ‘disharmonious energy’ if not a way of describing discomfort? Myth and magic are earlier versions of the same nets of understanding we cast over the world when we talk of cultures, political ideologies, even scientific paradigms – anything which concerns cause and effect. These more contemporary notions will capture the world’s contours more tightly than magical thinking, but in what they fulfil for us psychologically they are the same process of reduction, presumption, and eventual catharsis in feeling that we comprehend. Architectural determinism sits firmly in this domain.

The arts hold an ambiguous role within this, tending to affirm the power of a relationship between architecture and psychology while implying that this power has been used incorrectly, either through malevolence, as in Jean-Luc Godard’s 1965 noir-ish dystopia Alphaville, or through foolhardiness, as in 1974’s The Towering Inferno, a straight tower-of-Babel take on the danger of exceeding our God-given limits.

More interesting is Stanley Kubrick’s 1971 adaptation of A Clockwork Orange, which, in the same way that Alphaville created a futuristic city while using only shots of real Paris, portrays an eerie and ultraviolent London by using the new and often brutalist housing estates emerging around the city. This tapped into the period’s growing moral panic over ‘sink estates’ and large concentrations of generally working class people in government accommodation, the panic being the belief that these concentrations, for their design and density, bred violence and societal breakdown. Kubrik was famously obsessive about his locations and used this fear cleverly, seeing the estates of Thamesmead as apt for not just representing the alienation and latent aggression of modern urban life, as articulated keenly by Anthony Burgess in the 1962 novel, but a perceived form of psychosis emerging from it.

The vertical zoo

Another student of this ‘cultural psychosis’ was JG Ballard, and it’s worth lingering on his 1975 novel High-Rise, the story of the residents of a new and huge housing development in east London.

The inspiration for High-Rise is traced to varying things. The Hulme Crescents estate in Manchester is often cited and was widely considered a failed utopian social housing initiative. But the story comes perhaps more directly from a holiday Ballard had in a rented flat on the Costa Brava. There he noticed a tenant keeping self-appointed watch over the building to record the frictions between people on the lower and upper floors, rubbish thrown between balconies and other misdemeanours. Ballard said he was fascinated by not just the friction but by the compulsions of this man, ‘Some guy who’s probably a dentist, so obsessed with the sort of hostilities that are so easily provoked’.

High-Rise sidesteps the ‘sink estate’ issue so political at time by being about the people in that holiday block: the middle classes. Ballard was long interested in this group, their professional castes and what he saw as their hypocrisies and hidden, combustible natures. In making his high rise private and in many respects ‘luxury’ he does something deeply speculative and which may have seemed nonsensical at the time, when high-density housing was associated with the poor, but it was in the end highly prescient.

The three central characters are Royal, the architect of the building, living on the top floor just like Goldfinger lived for a time in his own Balfron Tower; the cool, reserved Dr Laing in the middle; and rough film-maker Wilder on the lower floors. A common reading of the building’s civil disintegration is to cast these characters as the nodes of the Freudian intellect, with Royal as the super-ego, Laing as the Ego and Wilder as the id. This particular melding of mind and architecture can be seen too in in Slavoj Žižek’s reading of the Bates house in Psycho, with the super-ego of Norman Bates’s pressuring and controlling mother upstairs, the ego of his regular life on the ground floor, mediating the competing interests of the outer world, and the id of we-all-know-what in the basement, that ‘reservoir of illicit drives’, as Žižek puts it.

Key to a psychological reading of High-Rise is its foremost character, who (amid the less subtle namings of kingly Royal and wildman Wilder) is called Laing in reference to badboy psychiatrist RD Laing. He controversially saw the social, and in particular the home, as the seat of human psychopathology, where everyday interactions represent manifestations of deep competitive instincts. In this context of buried aggression, which Laing believed was most complexly and damagingly repressed in the evolving middle classes on the 1960s and ’70s, mental illness could become a transformative journey, playing an almost shamanic role in guiding the ‘ill’ traveller in entering pre-social, animalistic regions to return with important insight. For these ideas Laing became a pariah to the mental health establishment and a hero to the countercultural movement.

Life in Ballard’s high rise breaks down to a tribal and competitive state, and, crucially, this is not viewed as a problem. The occupants wilfully seal themselves off from the world with their aggressions aimed only at each other, their violence not a rejection of the broader situation but an expression of their approval. Goldfinger wanted architecture to show people how to be less materialistic; the joke of High-Rise is that Ballard did just this, but in removing the shroud of the occupants’ materialism, what’s revealed is their murderously competing drives. It’s no Lord of the Flies, where the stripping of resources causes the goodguys and badguys to be uncloaked; the tower’s occupants are equal in their bestial instinct. Oblique little eruptions of this were seen in their earlier bickering over bottles falling from upper balconies and nappies blocking rubbish chutes – the muzzled battlegrounds of the middle-classes – but having been subject to the high rise they are free of these things and can now vent fully, forever. With no desire to change this situation, despite its horror, they are in an important sense happy.

Therefore High-Rise, the most horrific story mentioned so far, is not a dystopia. To think it simply a celebration of breakdown, though, would be wrong. Ballard saw exactly the pressurised depravity it describes as a child in a Japanese prisoner of war camp in Shanghai, stating in interviews that seeing adults stripped of their authority and defence gave him significant insight into what makes up human behaviour. Yet this insight was a broader view than suffering. ‘I remember a lot of casual brutality and beatings-up that went on,’ he said, ‘but at the same time we children were playing a hundred and one games all the time!’ This mixture is key to understanding the ambiguity, and ultimately ambivalence, that he writes into the psychology of the high rise.

The novel does amount to something of a psychological study. As with Royal pondering on the ‘vertical zoos’ he had long been interested in designing and inadvertently built in the form of his tower, Ballard spoke of aspiring to writing of a scientific, observational nature, likely aware of and influenced by many prominent psychological experiments of the time.11Notably: 1) John Calhoun’s rat experiment, 1962, where rats living in dense proximity were shown, despite having everything they needed, to kill and eat each other. From this Calhoun coined the term ‘behavioural sink’ and the experiment gained much coverage in terms of the ’sink estates’ moral panic (and, implied by the newspapers, the inherent violence of poor people). Ballard’s daughter said he would have been aware of the study, and would have seen it first-hand in her murderous pet mice in a cage in their living room. 2) Philip Zimbardo’s infamous prison experiment, 1971, where students were assigned roles of prisoners and guards in a mock prison. The situation soon broke down as participants conformed all too strongly to their given roles. This was ascribed to the self-affirming effect of the roles, no matter how arbitrarily given, with the participants’ psychological division deepened by the physical design of the prison. Likewise, Ballard rigorously stratifies the geography of the high rise by the professions of occupants, and in perhaps deliberately odd ways – airline pilots are the lowest of the low, while a psychiatrist is many floors lower than a gynaecologist at the top (though this last one may conform to recurrent aspects of Ballard that we’ll not delve into here).

But, despite having evaded the topical social housing question to instead explore the psychosocial realm, it would be a mistake to think that High-Rise is not political. There are few things more political, after all, than offering a reading of human nature. Where the Corbusian project had been the claim that design can improve people psychologically and politically, Ballard took an oppositional swerve into horror. Design may influence social practice, but for Ballard this does not have to refer to positive change. High-Rise is therefore a perverse affirmation of the Corbusian project and architectural determinism.

This determinism aligns more naturally with the environmentally defined world of the left, yet Ballard’s conservative position on the essential quality of human nature (that is, primal, not cultured) is preserved, because the building does not force a new behaviour on them; it merely reveals what was always there. This is morally and politically ambiguous in a way which has run through the core of the utopian tradition, that tradition being always about newness and so finding endless expressions in modernity. High-Rise, like the question of architectural determinism, is fundamentally and hauntingly modern.

Life out of balance

The so-called modern movement has inspired billions of dollars’ worth of ‘urban renewal’ whose paradoxical result has been to destroy the only kind of environment in which modern values can be realised.

So says Marshall Berman in his epic treatise on the growth of modernity, All that is Solid Melts into Air. He complicates things further, saying that the awareness and existential crisis of this destruction is itself part of modernity in that it forms the drive to create more, and in turn to destroy more. Moving into the 1980s we see that this combined sense of friction and introspection is fully ingrained in the popular discourse.

Godfrey Reggio’s 1982 documentary Koyaanisqatsi: Life out of Balance uses long time-lapse shots of cities and the frantic arpeggiated synths of Philip Glass to offer a sensory guide to the state of modernity. It shows the beauty of urban life with worshipful visions of skyscrapers and its corrosive side-effects through alienation and destruction, notably via footage of the 1972 demolition of the giant Pruitt-Igoe public housing project in St Louis. This project’s destitution was taken by many in the US to be a case study of the failure of left-wing politics,12It’s worth noting that in the same city as this huge social project there is the ‘Gateway to the West’, a modernist triumphal arch with a curious resemblance to one planned as part of the remodelling of Rome by Mussolini. This of course does not make the St Louis Gateway Arch fascist, but it does point to the political pliancy of modernist forms (with few such forms being purer than the arch). There is still a common denominator, however, and that is triumphalism. mirroring similar debates, and conclusions, in the UK at the time.

Koyaanisqatsi’s view is ultimately a pessimistic one, and in the ’80s we’re able to see how older ideas have been taken and adapted into a culture which is more circumspect and perhaps showing greater recognition of complexity. For instance, in conceiving the grand and polished infrastructure of the World State in 1932’s Brave New World, Aldus Huxley was inspired by some chemical works he knew outside Middlesbrough,13Though of course Brave New World resolved in other ways into what Huxley called a ‘negative utopia’, there being no such word as ‘dystopia’ at the time. And on the prescience-o-meter Brave New World scores astonishingly high, more so than the novel to which it is often compared, Nineteen Eighty-Four. Brave New World’s postulation is of an all-powerful state which does not need to ban books because people have no desire to read, which does not busy itself withholding information when the population is being flooded by it to the point that it acts as a kind of sedative. This is combined with the more literal sedative of widespread use of antidepressants and recreational drugs. Nineteen Eighty-Four had its more immediate prescience in Soviet Russia and the German Democratic Republic, but Brave New World describes something we are in the midst of and even now struggling to comprehend. yet in 1982 Ridley Scott used his memory of chemical works of the same company, on the opposite side of Middlesbrough, to inform the dirty industrial look of Blade Runner, a film which has been so aesthetically influential on all sci-fi since then, precisely for the addition of that dirt. The shifting trend in sci-fi from sleek to filthy was of course an expression of the awakening belief that our future will not be as rosy as we had collectively assumed.

A longer-spanning and extremely telling evolution is that of the panopticon. First proposed in the late eighteenth century by embalmed utilitarian Jeremy Bentham, the panopticon is a kind of prison wherein a central guard tower can see into each of the cells arranged cylindrically around it, the idea being that this ease of surveillance would require fewer staff. This worrying though frugal design was built only in a scattering of largely abortive instances. In 1975 maverick structuralist Michel Foucault published Discipline and Punish, in which the panopticon forms a model for understanding all society, not just in how the population had become so surveilled by vast intelligence networks but, more interestingly, in how this control had come to dictate – and inhibit – the very wants and desires of society. Foucault claimed that this inhibition stems from our belief in our own surveillance, from each other as much from the state, whether we are truly being observed or not: we are our own guardsmen.Another example of evolving dystopia, here more conceptual than aesthetic, is how Orwell’s Ministry of Truth becomes in Brazil, Terry Gilliam’s mad 1985 adaptation of Nineteen Eight-Four, the Ministry of Information, where the malevolence of the regime becomes subordinate to the absurd bureaucratisation of information. Mind-control is here less a diktat of ideology and more the by-product of the massive inefficiency and apathy of a world where there is simply too much information to deal with.

The genesis of this idea, from Bentham’s architecture to Foucault’s structuralism, makes clear what has been implied by everything raised so far. Namely that to talk about the impact of architecture on our psychology is really to talk about the society contained by that architecture. In conjuring an image of our future, whether utopian of dystopian or neither, the literal and metaphorical uses of architecture will collapse into one another. The greatest planners were aware of this from the beginning.

Satan’s lay-by

As the UK’s new town initiatives continued into the 1970s and ’80s, it was clear that they had become exactly the detached London suburbs they were intended to avert. Their garden-city genes stated that they should be mixed, egalitarian communities, but without the planned infrastructural skeleton for this they had instead turned into shapeless commuter hubs, bastions of a working class conservatism that would have perplexed Howard. They were roundly criticised for lacking identity.

From this criticism emerged the last, largest and most radical of the new towns: Milton Keynes. The ‘father’ of Milton Keynes was architect Derek Walker. He revisited the garden city ideal, planning a ‘forest city’ with residential estates bordering a planned central zone, entirely commercial and with a long glass shopping centre in its middle. This has made the city 14Though it has no such official status, it’s referred to as a city by locals, perhaps because its boulevards seem so synonymous with the idea of the grand urban layout – even with these symbols of modern city design being so abhorred in Britain (perhaps because their historical attraction for rulers, such as in Georges-Eugène Haussmann’s nineteenth-century remodelling of Paris, was in providing easy means for moving troops around). a regional retail mecca and is perhaps the key to Milton Keynes’s political ambiguity: the right disliked its large-scale centralised planning while the left disliked its consumerist economic focus. We see this confusion in Denis Thatcher, businessman husband to Margaret Thatcher, when he apparently praised the sprawling shopping centre, saying it ‘shows you what private enterprise can do’. It was of course built with public money.

This is a more contemporary iteration of the ambiguity we have observed across these utopian and generally modernist projects – and Walker’s design was overtly, unthinkably modern. As a final affront to the English psyche, it uses a grid system.15The perceived obscenity of this may be simply a function of having old cities, and therefore the grid system stands for uncomfortable change. But, considering the institution of grid systems in many large and equally old European cities, it could be that our aversion is something deeper, a romantic distaste for the essentially rational, calculable, and conceptually cold. The coils of the unreformed feudal settlement’s roads are an imprint of the English will to take comfort in chaos and amusement in inefficiency. Road names of obscure and at times absurd origins, like the words of the English language itself, chime better with this will than does the reasonable but shallow Cartesian coordinates of the grid system, those X-Y axes to which the modern aesthetic so often returns. As well as grid systems, Le Corbusier’s remodellings made heavy use of his ‘Cartesian skyscraper’ design, a massive cruciform block which looks from the sky like those axes of the mathematical graph. The result, as used in, say, Ville Radieuse, is a sort of graph of graphs: all measurement and no subject.

Let us be frank: Milton Keynes is the butt of many jokes concerning blandness and its inexplicably famous concrete cow sculptures. But what’s odd is that the characteristics which give it this perceived blandness are the very things which make it one of the weirdest places in the UK. Making it so apt for our purposes is that Walker, like Howard before him, had a keen sense of the non-literal, non-physical power of urban planning.

This is to say: there is a lot of highly peculiar pagan-ish stuff going on in the make-up of Milton Keynes.

The spine of its grid system is three roads: Silbury Boulevard, named after a man-made Neolithic hill; Avebury Boulevard, named after an enormous henge and stone circle complex of roughly the same period; and Midsummer Boulevard, which runs, the architects ensured, along the exact line of the midsummer solstice. The thinking of this seems to be that on midsummer morning the sunrise will flood through the boulevard to shine off the entirely reflective facade of the train station at its end. Midsummer Boulevard is considered to be on a ley line16Ley line: the mystical and New Age associations of which date back only as far as 1969, when author and ufolosit John Michell combined the older conception of ley lines (as simply paths linking ancient sites of interest, itself an idea dating back only to 1921) with feng shui. For anyone wondering whether ley lines ‘exist’, therefore: in the more prosaic sense, yes they do. running north-east through a park built along with the centre, over a landscaped hill modelled seemingly on Silbury, and eventually directly through the nave of a ‘tree cathedral’. Beyond that the parkland continues with scattered monolithic stones and a turf maze modelled on a famed Rosicrucian example. Walker is alleged to have redesigned a sewage works over a weekend in order to arrange it on a ley line connected to Avebury. Equally, the entire orientation of the city is so that it points, sixty miles away, to Avebury, the true start of the Midsummer Boulevard ley line.

This is all obviously catnip to conspiracy theorists, particularly those of the religio-occult variety.17It’s rumoured that in the ’80s a Christian group put the town under sustained investigation, believing it a hotbed of Satanism. In 2005 the city held a festival of Satanic music in a leisure centre. How times change. Illuminati hunters, meanwhile, point to Milton Keynes’s profusion of pyramids and domes as proof of its links to the New World Order (being built largely in the ’80s, when postmodernist architecture was trendy, there are a lot of monumental motifs), as well as to its many odd statues. The Internet People also allege that every street on the town’s Crown Hill estate has a name linkable to the Illuminati. But the sadly non-Satanic truth is that Walker, anticipating a backlash against his new town on the grounds of lacking the authentication of time, sought to ground it in the history of its region by using those deepest pre-Christian piles. These symbols and mappings are not (as the dowsing-enthusiasts would have you believe) paranormal resonances; Walker spent a weekend redesigning that sewage works, knowing that in all likelihood nobody would discover or care why, because there was in this act the wrangling of a strange and perhaps very English kind of authenticity. Its by-products are the code-riddled church, the pre-ruined folly and sprawling hedge maze, the hundred-foot hill figure forgotten to all but the birds.

Laing muses in High-Rise:

The cluster of auditorium roofs, curving roadway embankments and rectilinear curtain wall formed an intriguing medley of geometries – less a habitable architecture, he reflected, than the unconscious diagram of a mysterious psychic event.

Web of assets

Is this symbolic mapping, so historically vital to our relationship with our surroundings, being carried by our current designs and into the decades ahead?

A glance over the world’s mooted visions will reveal all sorts: the by-now classically futuristic hive-city all-in-ones of Shenzen Cloud Citizen and the Shimizu Mega-City Pyramid; the semi-sentient tech enclaves of Masdar City and L Zone Smart City; the generally buoyant ecological-cum-survivalist efforts of New Orleans’s post-Katrina NOAH and the curious Seasteading movement; and of course the Ozymandian follies of Kingdom City and Khazar Islands.

It seems that at least engineering marches steadily forwards (and public relations streaks into the dark horizon), but I am perhaps subject to my cultural biases when I feel that something is missing. Clichéd though it is to call a new building soulless, it’s specifically the idea of the soul, that beautiful nonsense-dream which has girded the most serious and worldly endeavours, which I find myself looking for, that vision which is at once enticingly symbolic and practically social.

Perhaps a notable difference between those mega-projects of our near past and these of our present and future is that these are driven fundamentally by private enterprise, and where they are not built by this (as in when oiled by the state petro-monarchies, etc), at the least their square footage is on completion yielded straight to luxury retail zones and corporate regional outposts. And yes, fusty are the old Marxist social utopias and Victorian philanthropic communes, Howard with his ‘farms for epileptics’, but following a century of variations on the authoritarian theme we find ourselves at the opposing extremity, amid the abandonment of any impetus to manage the collective psychology. Even this phrase, ‘manage collective psychology’, can’t escape a certain disquieting ring to the twenty-first-century ear.

Today’s social contract is bound by capital investment; the imperative to civil behaviour is driven through one’s place in a web of assets – whether one in fact owns any or not. The hypothetical luxury blocks of High-Rise are now real and stand as sentinels to a process which is recasting the social make-up of my city, London, in a way that, despite two millennia of ups and downs and essential endurance, seems inimical to the dynamism which has made that endurance possible – the sparks which leap from overlapping cultures and income-brackets. These blocks are part of the same web of assets, the same portfolios sitting as capstones on property markets, the same physical holding currency fondled by financiers and screwed into the economic machinery which drives the mega-towers up from the silt of distant man-made islands. Whatever utopia or dystopia they portend is therefore inseparable from London and every person in it.

The hulking economic complexity of this is enough to make one wish to escape to the cathartic reductions of a story, perhaps one about a terrible future lived in strange massive buildings. In the face of our present, dystopia has of course lost its power to shock, with ‘young adult’ fiction and film today full of its comforting simplicities. But instead of complaining at this, we might wonder how the form could catch up with our current utopias to speak with insight of the present and prescience of the future.

The end, the beginning

Look to Foucault’s extension of architecture to societal metaphor; look to High-Rise’s switching of architectural interior to psychological interior. Look (if you weren’t already) to your phone. The architecture by which we are determined will be decreasingly physical: the silent hypermalls of online transaction; the unthinkably fast transit systems of social media; the glitching archive-cities of open-content information stores; the towering sensory cathedrals of video and music streaming services. Building developers become software developers. Already the geometries which have shaped our lives are dissolving into a digitised internal existence which encases us from our neighbours yet reveals an infinity of floating voices.

Increasingly we will see these technologies developed into the spatial planes we have always been used to, but bound in virtual reality to no physical laws and so eventually capable of structures which transcend all current abstraction. The utopians are no longer lone polymaths but squirreled into the research departments of multinational tech-giants with lavish and infantilising employee perks; the dystopians are no longer politically inflamed subversives but hacks clacking out template fiction or with production companies’ costs to recoup at the multiplex, one computer-generated explosion at a time.

But at least everyone’s busy. What’s certain is that right now the planners are far ahead of the artists, who have largely failed to equip themselves to see over this peak we are traversing and to the pitfalls on the other side. The peak, though, is hardly new: we’ve been crossing it for a hundred years, the digital revolution dragging us only along the final stretch. Still, the cognitive shift it represents could not be more profound: having spent much of our existance transposing our thoughts onto the landscape, we now hinge at a point where we begin to transpose the landscape into our thoughts. After a while it may be that the outside, that tactile but limiting world, will become the less real of the two. We may never wish to return.

In 1985, Ballard said:

The only mode of reality now is inside our own heads, that’s the only thing we can trust. And surrounding us on all sides is this massive bank of fiction. Even the English countryside and most of the countryside in the Western world is totally artificial, what with factory farming, landscaping, concrete cows at Milton Keynes, colour-coordinated nature trails. To a large extent it’s impossible to say that the external landscape is anything but a fiction.

Notes