‘What do I like?’ we ask ourselves. And then, if we’ve not already opened the relevant streaming service: ‘Why do I like it?’

The need to divide the art we consume, to reduce to base elements and arrange into groups, is an old one, and takes seemingly as many forms as the art it concerns. ‘What do I like?’ is at once the shallowest question of the self – ‘What shall I buy?’ ’What should I be seen to consume?’ – and the deepest: ‘Who am I?’

Genre provides us with a set of answers to choose from.

So what does it mean that genre categories – our fillers of time, markers of selfhood – have hugely diversified in recent decades? What does it say of us, as consumers of art and stories, that the fanciful, the unreal, is more and more the answer we choose?

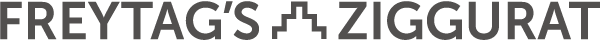

The genre continuum

You might offer a sociological explanation for our inclination towards genre, one that collapses the difference between ‘high’ and ‘low’ art to essentially talk about group behaviour. Taste is after all highly susceptible to social milieu and no one is above signalling what they consume. In this way genre might be read as an extension of evolutionary biology (although it’s unclear whether genetic survivability is increased through cosplaying with steampunk fans).

You could explain it with an appeal to psychology: ‘categorical perception’ is the assigning of distinct categories along what in reality is a smooth continuum of change. Taken from linguistics, where it’s used to understand speech recognition, the theory has been applied to other sensory areas like optics (a rainbow looks to us like demarcated bands of colour, for example, but is in fact a continuum of wavelengths without bands) and conceptual ones like aesthetics.

In this way our attentions ‘zoom’ into categories of interest, generating sub-categories within them that to other people, with their own focuses elsewhere, have no meaningful existence at all. Failure to distinguish between black metal and death metal would be quite the faux pas in metal-listening circles, let alone between industrial J-metal, symphonic grindcore and neo-pagan electrothrash. The further from your interests these are, the more similar they sound. Hence they sound the same to most people.

Wandering aesthetics

Another metallic genre, science fiction, has a similar habit for naming the regions along its continuum. This really got going only in the early 1980s, however, following a turn from writers like William Gibson and Bruce Sterling towards sci-fi set in the near future, rather than in some distant time and galaxy. This had its antecedents across the 70s as technology seemed clearly to be going in a direction different from gleaming Jetsons hover-cars and towards personal connectivity, and sci-fi generally got a bit grubbier. But Gibson could grasp the technical developments of the moment, imagine near-future applications and – crucially – how it would feel to live in that future, which in his visions saw narcotic countercultural sensibilities colliding with rampant corporate power, 70s with 80s.

This led to the short story ‘Johnny Mnemonic’ in 1981, the novel Neuromancer in 1982, and the genre later dubbed cyberpunk. The branching subgenres of sci-fi that we know today owe much to the aesthetic tools provided by cyberpunk – because Gibson (and this is important) is an aesthete, in a way very few fiction writers of any kind had been. The recontextualisation of aesthetic categories is essential to the way genre has since proliferated.

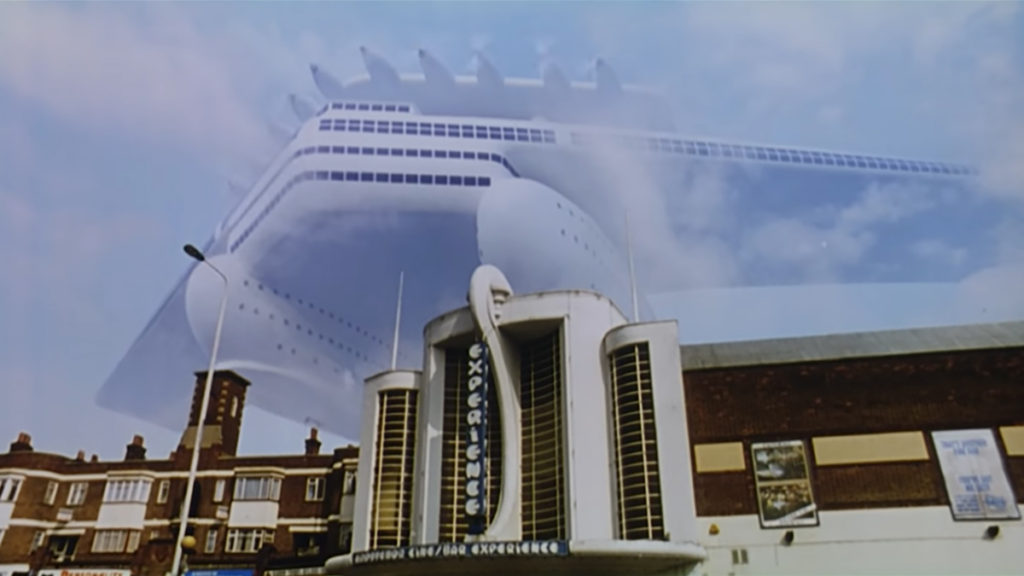

‘The Gernsback Continuum’, also published in 1981, is lesser known than Gibson’s cyberpunk works of the same time but no less important because it laid down a key method by which genres would split further. The story describes a man racked by hallucinations of a ‘flying-wing liner’ and ‘shark-fin roadsters’ on bleary California highways, futuristic and technological accentuations of a sleek art-deco and associated styles: streamline moderne, googie. This hybrid techno-aesthetic itself becomes the story’s subject, of being pursued by nostalgia for a past that never happened and a future that never arrived, and is even tentatively named within the story: ‘raygun gothic’. This is significant because it was one of the first texts in which the future was placed in a particular past, fusing them. This is now called retrofuturism1If you look up definitions of retrofuterism you’ll often see far older examples cited than ‘The Gernsback Continuum’, such as The Jetsons and the 50s and 60s futurology that inspired it, and even Metropolis in the 1920s. But I wouldn’t call those meaningful examples because they weren’t in any sense ‘retro’ at the time they were conceived. They were simply visions of the future, not visions of the future that consciously employed their own past.

In 1994, Gibson and Bruce Sterling3Who had in the mid-80s published Schismatrix, the biological focus of which (extending from the body augmentation seen frequently in cyberpunk) makes it one of the precursor texts of biopunk – a genre that I suspect might gain more prominence in the next decades as applications from synthetic biology become more central to everyday life. published The Difference Engine, an alternative history in which Charles Babbage brings advanced mechanical computation to Victorian London, and went on to inspire steampunk, one of the most ubiquitous sci-fi genres alongside cyberpunk. Steampunk propelled retrofuturism more widely, spawning cattlepunk (advanced steam technology in a Western setting)4The urtext of which is actually 1999’s much maligned Wild Wild West – for which Will Smith declined the lead in much celebrated cyberpunk filmThe Matrix., clockpunk (advanced Renaissance-era clockwork technology), dieselpunk (a dirtier WW2-based variation on atompunk, itself a dirtier raygun gothic), and many others.

As for the ‘punk’ suffix, tvtropes.org describes it like this:

A world built around a particular technology that is pervasive and extrapolated to a highly sophisticated level.

A gritty or transreal urban style.

A cyberpunk-inspired approach to exploring social themes within a Speculative Fiction setting.

My own sense would be that ‘punk’ genres are joined in their direct addressing of these categories – world; style; approach to social issues – while not necessarily coming to the same urbanised and nihilistic answers as cyberpunk. The categories are the ‘aesthetic tools’ that it provided, the fields that must be filled. Today’s sci-fi varies considerably in its answers, but writers’ readiness to take these base elements and generate new genres is in large part down to the departure that cyberpunk made5Solarpunk, for instance, was created in opposition to cyberpunk, imagining a verdant and ecologically minded cityscape, with a bit of art nouveau and afrofuterism thrown in. There in fact aren’t many examples of it, but this is relatively common for the nicher genres. The genre in this instance precedes the artwork and is given primacy over it, introduced in manifestos as if nearer to a 1920s artistic movement than a type of story, and concerning not just how the reader should read but how they should live. This is a presage of what will be discussed later., enabling ever new categories along the genre continuum.

But while this accounts for a particular proliferation of genres in the wider genre of science fiction, it cannot explain how examples within these genres still vary so widely. For instance Neuromancer, on top of everything else mentioned, is an adventure narrative, a thriller, and within that a heist narrative. It’s clear that genres interact with one another inside a single work. This means the continuum has multiple axes.

The genre continua…

Such complexity is in part because what we think of as particular ‘genre’ is not just a set of tropes – events, characters, objects, all the material goings on – but methodologies. ‘Gothic’ may make people think of haunted houses and wailing in the night but it’s also a method for building suspense and manipulating imagination through withholding visual queues, and often tied to a single location or structure. That method can be applied to different bundles of tropes to form gothic horror, gothic fantasy, gothic sci-fi. Event Horizon is a haunted house story with a spaceship instead of a house.

A distinction between method and setting is useful to a degree, but in truth any element could sit on any axis (similar to how any story can be reverse-engineered in the old elevator pitch style: Event Horizon = The Evil Dead + Forbidden Planet ) and, since the line between genre and trope is thin, there can be as many axes as there are substantial trope contributions to a story (Event Horizon = haunted houses + gateways to Hell + creepy alien worlds + stories based on The Tempest).

In the same way, Star Wars is superficially science fiction but is built out of mythic archetypes – whether from Joseph Campbell and Carl Jung or recycled from Flash Gordon – and takes the format of a Western: wandering heroes in a gritty and lawless place, fighting the encroachment of a large and malign governance.

The Western, despite famously being based on a very short period of history, and a highly specific set of social and geographical circumstances, arguably permeates genre storytelling more than any other, likely because it describes a foundation myth of the last century’s great factory of stories, the United States of America.

But to make claims on the origins of story-types would be a trap. The spaghetti Westerns of Sergio Leone explicitly emulated – as Star Wars also did – the samurai films of Akira Kurosawa, and so those myths that seem so idiosyncratic of a formative USA, of self-reliance and ‘natural’ justice, are in part built from the entirely separate mythos of Japan’s shogun past. A New Hope draws many character and narrative elements from Kurosawa’s The Hidden Fortress, while A Fistful of Dollars was based on Yojimbo and The Magnificent Seven on Seven Samurai.

In turn, several of Kurosawa’s biggest films were based on Shakespeare: Throne of Blood from Macbeth, The Bad Sleep Well from Hamlet, and the incredible Ran from King Lear. Shakespeare, of course, nicked stories from everywhere.

Genre is a messy concept, perhaps because it’s at once forward-looking, used to guide the creation of what’s yet to be, and backward-looking, a bid to make sense of what has gone before by picking over its remains. In this sense there’s something nostalgic and even regressive about it. Cultural critic Frederic Jameson singled out Star Wars as a postmodern pastiche of mid twentieth-century culture and aspirations, an attempt ‘to return to that older period and to live its strange old aesthetic artefacts through once again’.

There is something paradoxical about making a new contribution out of old things, but Star Wars presented such a density of older things, to such a huge audience, and at such a pivotal time in the transition to a more technologically connected, more culturally cynical and, yes, more marketised age, that I think it was part of something more complex than mere regression.

It signalled a change, not so much in the way stories are organised, as genre was by no means a new concept, but in the way we organise ourselves in image of genre. It’s this that allowed genre to become dominant in our conception of stories, and I’d suggest its rise has two fundamental aspects: one concerns new technology; one concerns new reality.

Genrification I: The desert of the real

In recent decades, sci-fi and fantasy have moved from being the reserve of social fringe-dwellers to the default mode of world-dominating franchises. A clear stepping stone was successful big-budget adaptations of long-standing material at around the turn of the millennium, including The Lord of the Rings and the first big Marvel films, making clear that these were stories wider audiences could enjoy, and that previous non-realist mega-franchises like Star Wars needn’t be isolated blips in the movie-release calendar.

Franchises and ‘extended universes’ make economic sense. If the initial films of a franchise are successful then its extended, pre-existing universe (adapted from old material, ideally with built-in fanbase) will mean that audiences are almost guaranteed, even if it’s promoted or reviewed badly. The feel of an extended universe, as opposed to a sprawling epic in the realist style, relies on a sense of exploration and so its reality will be separate to our own, different in technology, biology, physical laws. This means speculative storytelling of one form or another.

As to why it was the turn of the millennium when these blockbusters came about is harder to say, but we might ascribe the speculative boom of recent decades to a combination of: visual effects maturing to a certain level; the culmination of the 1990s’ ‘young adult’ trend leading to awareness that older audiences were happy to consume things in theory written for younger people, like Harry Potter; that the formerly bullied Hobbit-fans of the 70s and 80s were the ones sufficiently interested in storytelling to become a disproportionate amount of 90s and 2000s writers; and – perhaps – the way that a period of relative economic prosperity in the 90s collided with the confusions of the War on Terror to feed a desire for other, simpler worlds.

If stories are for ‘escape’, as some like to say, then it follows that only speculative stories can provide a faster-than-light exit from reality.

But, while simple escapism will certainly be the motivation for some consumers and there’s nothing wrong with that, it is by no means what speculative stories inherently are, and as a compliment on their power it is backhanded. Beneath this ‘escapism’ is a quiet but ongoing struggle over what stories are for.

Literary friction

Genre has long encompassed ‘realist’ styles, from crime fiction to romance, but it has also moved to annex parts of wider realist storytelling that historically required no particular label.

In fiction, this led to the concept ‘literary fiction’, a strange crypto-genre arranged around little more than a basically realist style (no silly outlandish stuff), an intent to be ‘good’, and an assumption that these things are in some way linked.

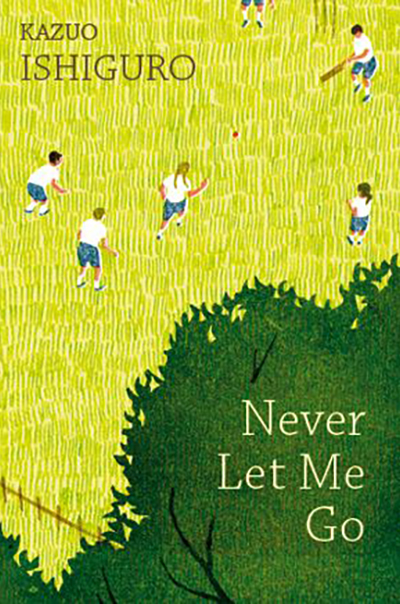

The main use of the ‘literary fiction’ label has been to identify exactly which part of fiction is dying the fastest. The august figures of British literary fiction have found their outputs adapting and things at times have got heated. When Nobel and Booker Prize winner Kazuo Ishiguro published The Buried Giant in 2015, he expressed concern that it might be written off as fantasy, sparking an angry rebuttal from Ursula K Le Guin, a rebuttal of the rebuttal then some writerly de-escalations. Ishiguro to his credit accepted he had almost inadvertently entered a pre-existing genre (he had been thinking of Arthurian legend and Beowulf when writing, accepted parts of the ‘literary’ canon essentially because they are old6It’s possibly a crude presentism to call these fantasy works, since distinctions between the ‘real’ and ‘fantastical’ worlds have changed over the course of human history; but equally it would be silly to state categorically that they aren’t. Because, you know, monsters.) and then with humility sought to understand it.

Ishiguro in 2017 won the Nobel Prize in Literature, the ultimate blessing of the literary establishment, essentially while writing genre novels. But you won’t hear him being referred to as a genre writer.

A somewhat different case was in 2019 when Ian McEwan published Machines Like Me, about a life-like android. During the promotion, it didn’t go down well when he implied that the conventional sci-fi of ‘travelling at ten times the speed of light in anti-gravity boots’ is mutually exclusive to the study of human dilemmas. And it’s true that mainstream genre storytelling has too often leaned on pre-modern notions of good versus evil. However, all stories, even the pulpiest sci-fi (like all those Pinocchio-style AI tales of the kind done to death for seventy years – who’d write another one of those, eh?7In fairness Machines Like Me’s setting of a retro-futurist 1980s Britain sounds interesting, using a vision of early computing more advanced than was truly the case. Does McEwan know it’s called cassette futurism?), are explorations of human dilemmas, whether unoriginal or insightful, and appealing to older or newer worldviews.

To insist that the exploration must only use certain tools in order to qualify as an ‘exploration’ at all is to elevate the failures that will arise by those means and ignore the successes by others. Methods differ, but quality, and ‘literariness’, are separate variables.

Please, sir, I want some more

This assumption within literary fiction – that serious storytelling must be realist – is old, but not that old, because neither is realism. Like any idea about how stories should work, realism was the product of a set of historical circumstances in only certain parts of the world. What’s more, the arguable end of realism’s dominance may tell us something about how contemporary storytelling has changed.

Across the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, the principles of the scientific enlightenment (worldly observation, seeing and presenting things as they are) were taken up by artists of Europe and America, foremost in France and Britain. Among the results was the bringing of everyday subjects and characters to the fore of stories, placing them as worthy of attention. Readers raised on the deeds of Perseus were now reading about Oliver Twist. After a long (and relatively global) tradition of royal and high-born heroes, this was revolutionary.

But this new style far outgrew its alternatives. Some critics have argued that the novel as a medium only really took form through realism (distinguishing it from ‘romances’, or tales of the fantastical), and this was what allowed contemporary stories to be treated for the first time as seriously as the classics. People couldn’t get enough of realist stories in part because they couldn’t get enough of the medium that carried them.

If true, this presumed synonymity between realism and the novel may have had a distorting effect on the European and American sense of the ‘proper’ way to tell a story, biasing it towards a distinctly Western worldview and obscuring the fact that, within the West, fantastical stories were still read in large quantities.

Victorian adults read fairy stories without any assumption they were intended for children. Readers in Britain and France were enamoured by tales from the Arabian Nights8Among which are precursors for the genres and speculative tropes we know today (interplanetary travel, underwater cities, murderous ghouls), while themselves being a consolidation of older stories from across Asia, Africa and Europe., and long predating the Victorians was the assumption that the Greek and Roman classics should form the basis of a gentleman’s education. Yet these are awash with snake-haired women, magical babies suckling on wolves, and quite a lot of impregnation-by-bodily-transmogrification. These tales spring directly from the bedrock of ‘Western civilisation’ yet in isolation read like fantasies from the darkest corner of Reddit.

The fantastical is in many our default mode of seeing. But the novel continued its mass-market dominance into the twentieth century, and those strange old stories – not least those of a key speculative work: the Bible – diminished in circulation as the West secularised and scientised. Responses to realism gained some recognition over the decades but couldn’t offer an alternative to realism, be they literary modernism (too many three-page sentences) or magical realism (too many people floating off into the sky for no reason). These offered only diversions.

Grand narratives

The 1980s saw the beginnings of change, first in academia. Postmodern and postcolonial literary theories grew, seeking in their different but complementary ways to tear down the ‘grand narratives’ of the Western canon.

Postmodernism transitioned neatly into 90s mainstream arts, from the achronological structure of Pulp Fiction to the false reality of The Matrix, and was bedded in the slacker sensibility that defined the decade’s culture, and which arguably was a side-effect of living at the economic apex: the privilege of boredom. ‘We have no Great War,’ says Tyler Durden in David Fincher’s adaptation of Fight Club. ‘No Great Depression. Our great war is a spiritual war. Our great depression is our lives.’

The ideas behind postcolonial studies, on the other hand, only broke into the Western mainstream in the 2010s, with – I would argue – significant impacts on culture and politics.

Through these shifts, it became axiomatic that realism never showed things as they are, only as they appear to the dominant perspective. The grand narratives of storytelling toppled alongside the grand narratives of lived experience9American literary critic Fredric Jameson famously called postmodernism ‘the cultural logic of late capitalism’ for its rejection of grand narratives that critique capitalism, therefore doing capitalism’s work for it. Physicist Alan Sokal had an article full of deliberately nonsensical postmodernish language accepted by a journal as a stunt to show how meaningless trend-driven postmodernism is. These attacks aren’t without merit: while ‘trendiness’ can be a lazy and ad hominem criticism to make of something when it comes in place of substantial argument, it is difficult to deny a certain amount of bandwagon jumping when it comes to ideas making that treacherous transition from academia to mainstream culture. The question is of what is lost in that process, what the keen new disciples have unknowingly failed to understand, and what collateral damage may arise as a result (arguably this has been the case with postcolonial studies in particular). Equally, the critics decry postmodernism from worldviews which are themselves shaped by contributions of postmodernism, comfortable to reject the prevailing cultural narrative because that narrative itself concerns the rejection of narratives (the sort of postmodern paradox that raises a smirk or grimace, this response largely dictating which side of the argument one falls on), and possessing the linguistic craft needed to take it on only as a result of postmodernism’s focus on the primacy of language, imbuing this into the wider culture. Postmodernism is perhaps more closely described as the cultural logic of advanced communications technologies. Nonetheless, it has become a bogeyman of the political right, based largely on a confusion between postmodernism and moral relativism – a philosophy adhered to by precisely no one. Occasionally you might hear a commentator or even politician attempt blame put all the world’s ills on Michel Foucault.; changes in communications technologies enabled alternative viewpoints and alternative facts to flourish, be they fraudulent or nonsensical or actually quite possibly true – and the difference impossible to confirm.

Speculative stories’ shift from fringe to absolute centre of mass culture is both a symptom of and response to all this. And it’s the final, technological element, the internet, with its ability to provide ever more specific homes for users, which proved the greatest atomiser – and populariser – of genre.

Genrification II: The internet

Subcultural groups were once clearly demarcated with standard-issue past-times, clothes and musical tastes from a limited menu of identities. In British sociology the literal textbook example is the mods and rockers of the 1960s, early ‘youth culture’ avatars from which evolved skinheads, punks and teddy boys. These changes really started in America, where by the 1980s youth subculture was already a matter of cliché, satirised in The Breakfast Club, and in Clueless in the 90s10The D&D-playing outcasts are not even in these movies, of course, presumably busy dry-brushing polystyrene rocks in their basements, but they are tellingly brought to the fore in more recent nostalgia-fests like Stranger Things..

The divisions these films played on remained real, but their knowingness and growing skepticism of the cultural pigeonholes in which young people found themselves indicated a desire for something more; as if ‘youth culture’, which had been so genuinely radical in the 50s and 60s, was no longer owned by young people and instead directed through the ad campaigns of multinational brands, commodified into nothingness while those gen-Xers were toddlers – and they knew it.

At school in the 2000s, however, the subcultural divisions appeared to me to be visibly reducing as people within friendship groups found easier access to cultural materials on their own online, along with communities that validated these interests, and the spread of tastes within social groups diversified. ‘Geek’ stopped being an insult. Now, young people still have their broad subcultures of the moment, but for a person to be into things that even their immediate friends are not appears more common and acceptable than could have been imagined in the 80s, when reading superhero comics was social kryptonite in many circles.

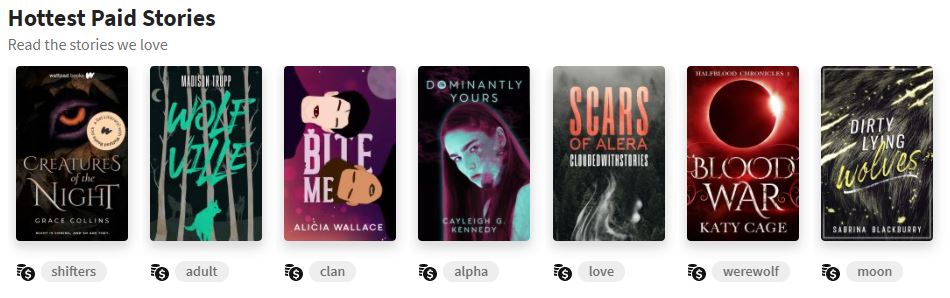

Having changed how culture is found, the internet then radically democratised how it is made and disseminated. Developments in professional-grade hardware and software, as well as in apps that allowed them to be downloaded and their licences ‘cracked’, put historically inaccessible disciplines such as filmmaking and music production in the hands of enthusiasts. The most important changes, meanwhile, were in distribution. The creation of online publishing platforms like YouTube, SoundCloud and Wattpad11Wattpad is mentioned because it represents one pillar of the arts – fiction – but differs from the others in that, while video and music platforms have precipitated varied ecosystems of content, as you’d expect, including stuff of as high a quality as published anywhere, the fiction platform Wattpad seems to have precipitated… werewolves. Unbelievable amounts of werewolf stories, of a style you might call ‘YA’ if generous, but also with sexual dynamics you might call ‘edgy’ if really generous, including the frequent romanticising of rape and sexual slavery. A niche set of tropes, yet seemingly repeated at massive scale, with tens of millions of reads. This is what humans have done with the YouTube of fiction. It warrants further investigation. linked creator directly with consumer, beyond the jurisdiction of traditional publishers.12Although, as much as this sounds like – and in many ways is – progress, these platforms and others are in part driven by exactly what drives the dinosaur distributors like commercial radio and TV: advertising. This is the grease in the machine, in a sense unchanged since the 50s. As to whether this is an inherently bad thing for culture or not, your answer probably maps directly to your political sensibilities.

Those publishers could no longer claim to be providing consumers with the best of what is current when art (AKA user-generated content) was being produced and consumed, at scale, before they even knew it existed.

Bedroom enthusiasts

The boundaries between self-publishing platforms and the wider culture industry became more complex as creators migrated back and forth between them. In this looser climate, writers of films, TV shows and games went deeper into the genres they loved but which had never been presented to quite the right depth for them, or with the desired aesthetic or setting. Non-professionals, meanwhile, took to the earliest self-publishing platforms built for fiction and found they didn’t need to leave their favourite pre-existing story-worlds at all, instead extending those worlds themselves and publishing the results in serial, maybe never finishing at all.

All this splicing of genre was in a way how it has always worked, and fan fiction is certainly nothing new, from excitable Star Trek fanzines to literary works like Jean Rhys’s Wide Sargasso Sea, written in answer to Jane Eyre. But the old desire to create just for fun now had the infrastructure to share as well. Highly specific communities could be built and reached directly, defined by tropes and tastes. If you happen to be into robot uprising stories, or dying Earth stories with an ecological moral, or stories were robots rise up during a dying-Earth scenario, or where all this happens but the robots also have sex with each other (since this is may the entropic endpoint to which much online fiction tends), then there will be likeminded gathering points for you.

But as spaces opened up in which ‘return on investment’ was not required, and new appetites were found in consumers, these appetites in turn became new markets by which investments could be returned. ‘Just for fun’ is big business. Massively successful bondage-thriller Fifty Shades of Grey was created from IP-stripped fan fiction of the massively successful chastity-allegory Twilight.

What’s interesting about this example is that EL James based the original fan fiction behind Fifty Shades in the Twilight universe except with the somewhat key element of vampires and the supernatural removed. This arguably runs against my wider point of a turn towards speculative stories across the 2000s, but it’s notable that switching out a supernatural framework for a highly sexualised realist one apparently worked well enough for readers. As if these things are somehow not altogether different.

Twilight rode a trend for vampires in the early 2000s, and it requires no smirking Freudian to see how sexual the trope of the vampire is and has always been. The series also helped usher in the Age of the Werewolf, which has largely supplanted the vampire. Arguably these monsters form the two poles of web-fiction’s psychosexual landscape – although speculation on what each means and why there has been a shift between them is way (way) beyond the scope of this study.

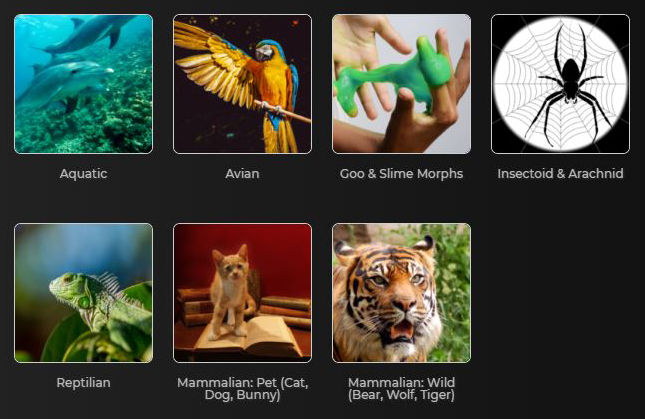

In any case, it’s conceivable that the splitting and spreading of genre mirrors – and is at some deep-conscious level connected to – the growing awareness and acceptance of diverse sexual proclivities, both aided through the rise of the internet. One of the biggest online publishing platforms to have emerged, and which my previous list was too prudish to mention, is Pornhub. In principle it works exactly as the others do, and has an equal habit for hyper-categorisation and unreality.

This suggests that not only is genre becoming more diffuse but, as with the growth in disinformation and conspiracy, the boundary between what is ‘story’, and what is not, is no longer clear.

Stream of consciousness

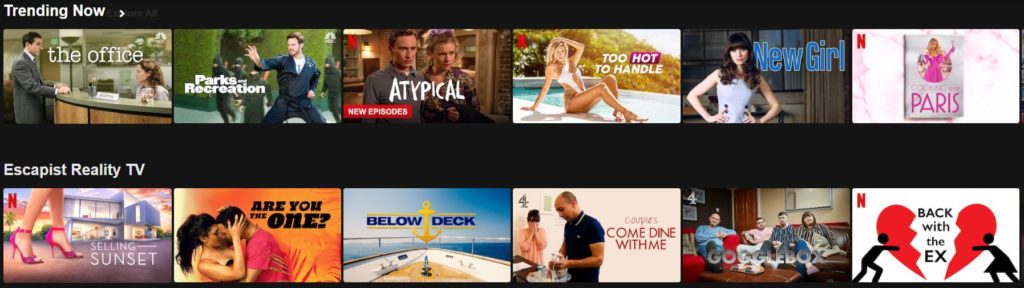

Still, though, it feels that changes in genre and storytelling are crystalised only when they go beyond the user-generated world to become the output of film companies and, to an even greater extent, streaming services14Hybrids are emerging, such as Wattpad employing algorithms to find highly marketable stories on its platform and feeding them through its own studios to create films and TV shows, with the original creators involved to varying degrees. Perhaps this indicates future models, but they would need to find a way to escape the narrow teen-romance confines that Wattpad itself is stuck in.. These services are not quite the opposite of more open platforms like YouTube, since they both represent a tipping towards the viewer, the user, in directing what the culture industry makes. But they differ in that the user-creator remains king on YouTube, and for the time being on social media platforms like TikTok, while Netflix is driven not by user choice, exactly, but by user behaviour.

First explored by Alexis Madrigal in a 2014 Atlantic article, Netflix’s ‘microgenre’ system in essence sees tags applied by hand to everything in its database according to criteria laid out in what at the time was a 36-page guide. These tags connect the content to one or several of tens of thousands of microgenres, which in effect are short descriptions of the material. Madrigal identified the syntax for microgenres as roughly:

Region + Adjectives + Noun Genre + Based on… + Set In… + From the… + About… + For Age X to Y

This has resulted microgenres such as Violent Foreign Musicals, Dark Canadian Dysfunctional-Family Dramas, and, obviously, Steamy Vampire Movies.

The point of microgenres is not to enable users to find ones they like and search accordingly for content, but to enable Netflix to characterise the content that a particular user watches, and through that hopefully very accurate and sensitive characterisation serve more of the same.

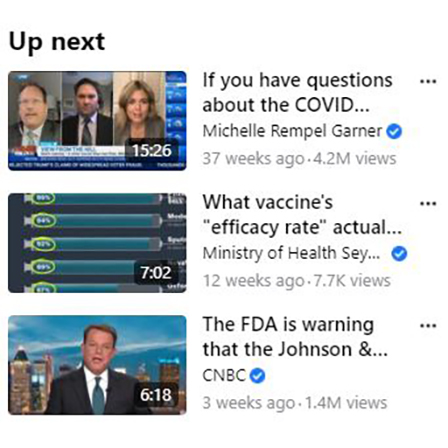

This algorithmic distribution of culture is by now the norm, and of course is no less central to user-contributor platforms like YouTube and its ‘up next’ algorithm. But the ‘microgenre’ terminology that Netflix applies to its own may offer a window on to the future of genre itself, since it shows us explicitly how the concept of genre can be inscribed on the algorithmic technologies that have come to sit beneath so much of mass culture, driving it.

This is not so much a means of sustaining an old-fashioned concept as of showing how it has evolved beyond our capacity to grasp it directly. Netflix is kind enough (or eccentric enough) to give us comprehensible and visible names to its microgenres, the components of its algorithm; others feel no need to tell us, and it’s probably better for the accuracy of their recommendations that they don’t, as our awareness might bias what we select.

At this point in time, our passivity is essential to our entertainment.

‘It’s gonna get easier and easier, and more and more convenient and more and more pleasurable, to sit alone with images on a screen given to us by people who do not love us but want our money’

David Foster Wallace, The End of the Tour, 2015

What should be noted is that all of this works exceptionally well, assuming the goal is for us to be entertained. It’s easy to take a snootily dystopian view of it, but the platforms are the digital fronts of entertainment companies. It would be strange, given what they are constantly learning of the behavioural effects of various functionalities in the platforms, and what these effects mean for their bottom line, if they did anything else.

But, yes, there is an undeniable grimness to it. The narrowing and sensationalising effects of algorithmic culture are well known by this stage, not least in the political bubbling that has shaped the last decade, almost everywhere in the world, segmenting people’s perceptions into parallel and seemingly impregnable worlds. It’s as if the only way to sift the internet’s impossible vastness (which after all is what such algorithms are for, in principle) is to give the impression of erasing all but the tiny portion deemed most similar to the user.

Of course, this is written off as teething problems, the result of immature algorithms. Datasets will be broadened, taxonomies of tags deepened, recommendations made to at least feel serendipitous. But as algorithms sift fiction and reality to present the most entertaining of each, the ‘solution’ to their deficiencies may involve no less a change in ourselves as consumers.

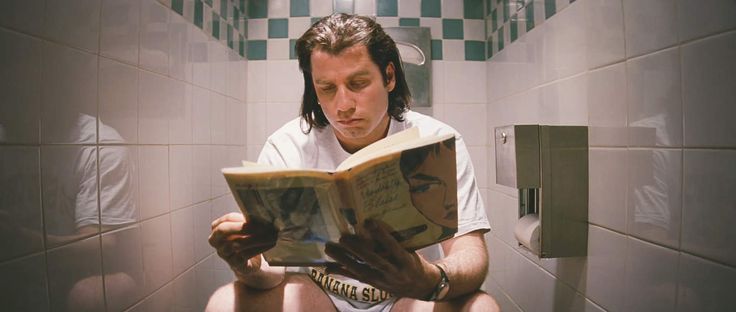

Mood music

Vinyl LPs turned on hefty living-room turntables, revealing albums song by song. Then tapes unwound in walkmans and CDs spun in car consoles. Then CD drives ripped and hard drives buzzed in teenager’s computers while Napster and BitTorrent amassed individual tracks into vast, ill-gotten archives.

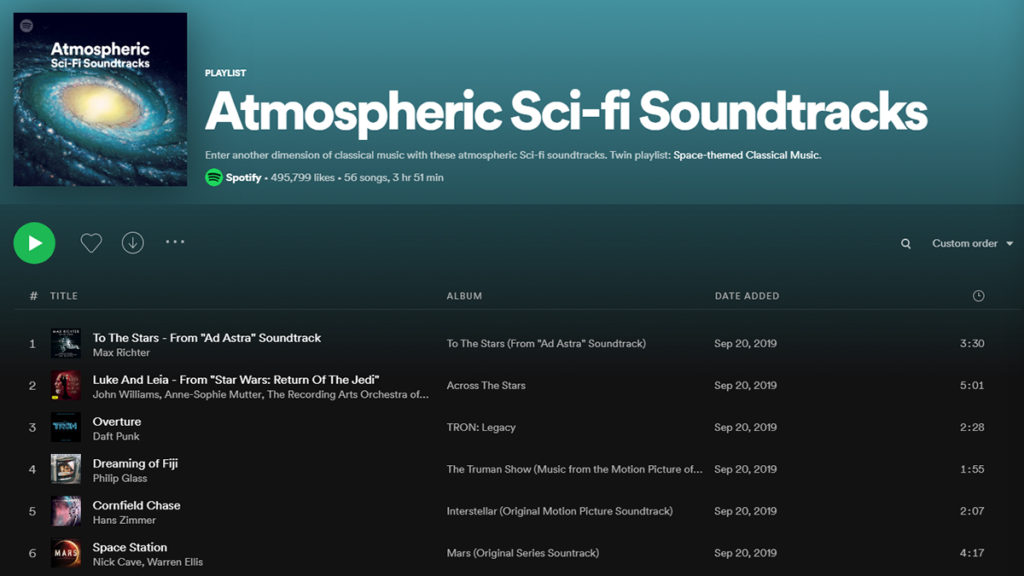

But then last.fm took a song and from it generated a dynamic playlist of songs you might also enjoy. Spotify derived weekly then daily playlists from your listening habits, curated others under ‘pop’, ‘hip-hop’, then later ‘workout’ and ‘mood’. YouTube precipitated live streams to study/relax to, mixes of Songs for Dead Planets, 12-hour loops of isolated background noise from Rick Deckard’s apartment.

Across this journey we see automation increasing, sure, but, rather than the machine takeover of the arts that some fear, as if Spotify is secretly controlled by some EDM-loving HAL 9000, all these more recent changes have still involved human curation, and we’ll likely be working with a human-machine ‘tastemaking’ model for some time. Like if Gertrude Stein worked for Skynet.

The real story of music’s recent interactions with technology has been of how our attentions have drifted from ‘active listening’, as is encouraged by a record, to enjoying song after song that we simultaneously are unconcerned to never hear again – because it is not the songs we are listening to but the mood.

This of course tends towards younger generations and so older ones may not recognise it, but, for many people, the boundaries of an individual song have blurred into the wider style that describes it; genre has become no longer an organisational tool but itself the art object, one that supplements and integrates with what you are doing, be it jogging, studying, engaging in recreational nostalgia for something not even five years old15For as long as there has been a distinct ‘internet culture’ to speak of, nostalgia has been central to it. The short-lived but influential chillwave music ‘microgenre’ emerged in 2009 as young people experienced the precarity of the financial crash, triggering a desire for the womblike simplicity of formative times, even – and perhaps especially – when those times were tinged with a certain sadness or loneliness. This cocktail might draw on soundtracks from old films, outmoded games consoles, essentially the trappings of a teenager’s bedroom. In the 2010s, Soundcloud rap (named, note, after the platform it grew out of), continued this yearning for innocence and engendering it somewhat absurdly in fans who were barely teenagers. The aesthetics of YouTube channel ‘lofi hip hop radio – beats to relax/study to’, mentioned above and influential at its height, are calculatedly steeped in nostalgia for teenage-bedroom safety. Of course, drawing on ‘authentic’ experience is arguably not the point; it is a performative tugging on the fruit machine of images and sounds that the internet offers, collapsing generations and time. Nostalgia is perhaps an inevitable result of – even a sort of defence mechanism against – information overload., or gazing into the abyss of space and time.

Ambient music has existed as a genre for decades, but what I’m talking about is all music, delivered ambiently. And while this has concerned the auditory arts, which leave your eyes and hands free to be doing something else, it may nonetheless be an indicator of where the wider concept of genre is heading.

Ambient culture

‘What do I like?’ we ask ourselves. ‘What kind of thing do I want to watch?’

Every streaming platform is built to answer this question, and the smarter ones will do so not just in more traditional, ‘active’ terms – ‘What type of story do I want to put my attention into?’ – but in the terms that many are truly now asking it: ‘What mood do I want to be in while I message friends and browse the internet on my phone?’

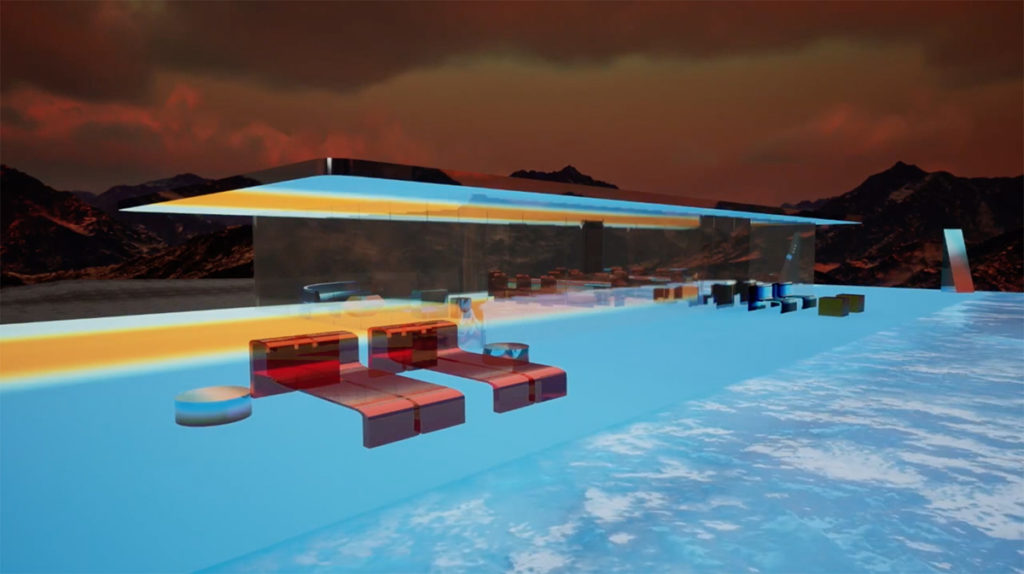

This is not the death of storytelling, or even of attention spans. It’s no coincidence that open-world games (which have become one of the dominant formats for computer games over the last two decades) are often appreciated more in terms of offering spaces to inhabit than whatever plot structures are built within them. The serial fetch-quests that constitute No Mans Sky’s storyline (added only after the game’s release) are insignificant for players compared to the technicolour gigantism of its explorable galaxies, made to evoke the kitsch wonder of Golden Age sci-fi novels. This is what the game is, just as Grand Theft Auto is its underworld American dream, Fallout is its bleak, irradiated fantasy of solitude.

The proliferation of genre made possible by the internet (and in turn the atomization of aesthetic sensibilities), combined with the high-volume content enabled by the streaming giants’ business models, and the keen organisation of their platforms, has allowed consumers to scratch what may be a very old itch: to live and think in a place other than where our bodies happen to be.

This goes deeper than getting lost in a good book. Even though, perhaps counterintuitively, it requires less concentration. It’s exactly the wandering of concentration that gives these ambient aesthetics greater reality, because it limits our conscious mind’s capacity to reject them.

There will always be diversity in how people absorb art, and the shift I’m describing of course neglects one of the oldest mediums: written fiction, which for most people does not play well with multitasking (and I believe, or hope, will always retain a special quality for that reason). But the shift is happening, even though some will abhor it, as some have for every historical shift in how art is consumed. They are left behind every time.

Cryptoculture

To disentangle the interactions between technology, profit motive and consumer desire that have tipped us towards an ambient culture, and find the single, primary driver, is not simple. But this three-way chicken-and-egg may at least be called ‘the market’, in broad terms. The market is the ultimate arbiter of the shift, as it was of the last and will be of the next.

I’m aware that isn’t very romantic or cool-sounding, but the market doesn’t need to be, as long as it’s subsuming and selling you the stuff that is. A way out of the market-driven algorithmic recommendation of culture may conceivably be if the means of distribution were themselves distributed beyond the corporate space, as cryptocurrency has done in finance through distributed networks where the infrastructure does not exist in one place and so is not owned by any one entity, while the digital artefacts on those networks very much are, and to more profound a degree than is otherwise possible.

But the art-objects of blockchain – non-fungible tokens – are not without problems, and nor is cryptocurrency. It is naive to think the market could never subsume them as well. And in any case, a substantial turning away from the mega-platforms would require people not being sufficiently entertained by what the platforms are serving them, and there’s no sign of that. Whether we’re happy, though, is a different matter.

Human kinds

The algorithmic distribution of culture has drawbacks, as discussed – the repetition, the narrowing, the social bubbling – and ‘genre’ in that context is as much a Babelian curse as it is a way for people to express themselves in sensibilities beyond those handed to them. And, as discussed, algorithmic distribution will likely be improved as a method rather than replaced. The Model T’s deficiencies did not do away with the car.

But perhaps it’s those individual human sensibilities that will be where genre develops. As stories have blurred with genres, and genres have blurred with how we feel, or wish to feel, it could be that the consumer ceases to stand on the outside of this, accessing it to pass the time, but joins.

The market already indicates this. Consumers are no less tagged than the content they consume, sorting us by ever more nuanced categories of consumption. What is the difference between consumers and content, functionally, to the platforms that match us with what we watch?

It may be not virtual worlds that we enter, but virtual worlds that enter us.

Pockets of activity long established, and somewhat maligned, but decreasingly so as the speculative world and its silly stories have been normalised, may show us a future where the mood of certain genres will bleed beyond what we like and into what we do.

See this in the subcultural aesthetes, the cosplayers, the tabletop and live-action roleplayers whose characters have quite genuinely meshed with their own personalities; further out on the fringe, for now, see it in ‘otherkin’ groups who identify as animals, mythical beings, abstract concepts, often drawn from certain story-types, and among them ‘fictionkin’ who identify as particular fictional characters.

These are stories inscribed directly onto the physical self, blended with behaviours and aspirations ‘in real life’, and offer an accentuated vision of something that may permeate more generally. Perhaps it already has, as technology so readily separates mind from body and then divides the mind across applications fictional, social, informational. How could these things not blend?

Consider what was strange a few decades ago but is now normal. And while there are differences between a cybergoth, a woman dressed as Harley Quinn at a convention, a level-6 paladin running around a forest, a man surgically altering himself to become an extra-terrestrial elf from the Pleiades cluster – are they not all speculative genres of human?

Notes