As we read or watch a story, it’s easy to think that its emotions are being somehow delivered to us, as if through the air. But they’re not. They activate only what’s already there.

This is also how drugs work: ‘agonists’ bind to a cell’s receptors, triggering serotonin warmth or adrenal shock; ‘antagonists’ block the cells from doing they wish, but are necessary for the system’s balance.1Story is itself claimed to trigger the creation of certain chemicals: oxytocin, which is associated with empathy and released presumably as the mind constructs fictional people to then chemically feel what they would; and cortisol, associated with concentration and perhaps the means of the tunnelling effect that allows us to focus on a page or screen as if it is momentarily the entire world. Stories might be acquired over the counter from careful specialists or through car windows from high-volume entrepreneurs, cutting with whatever’s to hand. But everyone uses the base molecules of characters, situations, objects of interest.

And among those objects, some storytellers will employ (since they like getting muddled in their own metaphors) drugs. The method is simple. To make you think of a pill, the writer inserts one. To make you aware of what it does, the writer tells you. To make you feel what it does, the writer constructs a narrative with the frantic pacing of hyperactivity, the fractured plotting of derealisation, the sensual language of euphoria, or whatever off-world experience they can synthesise. Call it mythopharmacology.

Here follows a brief history of fictional drugs and an A-to-Z of examples, with associated classes. This is hoped to aid our eager practitioners in avoiding infringement (or at least making infringement look like homage) and cliché (or at least making cliché look tongue-in-cheek).

Food of the gods

While pharmacology is ancient and its study widespread in the pre-modern world, older storytelling leans more towards enchanted foods and objects to deliver its altered states. Aside from drugs being generally far lesser in their effects (or at least less well targeted), and so perhaps less obvious as plot devices, drugs’ singularity of purpose may have rendered them less attractive to storytellers in a world that believed more firmly in hidden powers beneath everyday things.

Each of the pomegranate seeds eaten by Persephone in Greek myth consigns her to a stretch of time in the underworld, because all food and drink of the underworld, it goes, has some kind of opiate effect, trapping its consumer there. Meanwhile the food of the gods on Olympus – ambrosia and nectar – confers immortality to its consumer. When Tantalus tries and fails to steal these, his punishment is for food and drink to move always just beyond his reach (hence the verb ‘tantalise’), like addiction’s reaching in vain for those early experiences.

And there are of course endless power-granting objects. In The Republic, Plato presents a story of the Ring of Gyges, in which Glaucon finds in a cave a ring that grants invisibility, then uses this to kill a king and become ruler himself. This is used first to argue that virtuous behaviour is built on a fear of the consequences of behaving poorly, then that this is false and virtue is to behave in the right way no matter how free of consequence it may be to kill and usurp2The account of the Ring of Gyges of course bears a strong similarity to the One Ring presented by Tolkien in The Hobbit. In his letters Tolkien said curtly that ‘Both rings were round, and there the resemblance ceases’, but a ring found in a cave that permits its wearer to do evil does amount to a bit more overlap than roundness. Still, an important difference may be that the One Ring arguably adds evil to what was good, while the Ring of Gyges permits the evil that was latent. Both could be called corruption but with Tolkien’s a stronger form than Plato’s, which takes a dimmer view of human nature. This matches the difference between them: Tolkien, a Christian writer, believed in a duality of good and evil; Plato believed humanity’s natural deficiencies could be mitigated through abstract virtues and noble lies. (Or you could put it this way: Tolkien was a Bible reader; Plato was a Bible writer.) .

In these examples we see the neat little parables and lessons that magical items have long embodied. Some are neater than others: the godly foods show the individual seeking to change the composition of the world, of themselves, and ultimately the world asserting its fateful dominance over them. In the more nuanced, like the Ring of Gyges, we see a world without the comforts of some self-regulating cosmic redress and the reader being presented with a question to mull. This extends from a worldview strangely modern for its time, and it’s a method we see increasingly as we near the modern era and the magical objects of yore are reconfigured with the language of science.

Counter culture

The twentieth century saw developments in pharmaceuticals that allowed greater psychological intervention than before, giving rise to the sense that our very selves are a manifestation of chemical releases, balances and imbalances. Combined with the rise of psychoanalysis and psychotherapy, this caused a medicalisation of the blurred area between mental health and personality. Our dispositions moved from being a God-given state to a treatable organ, even an improvable device.

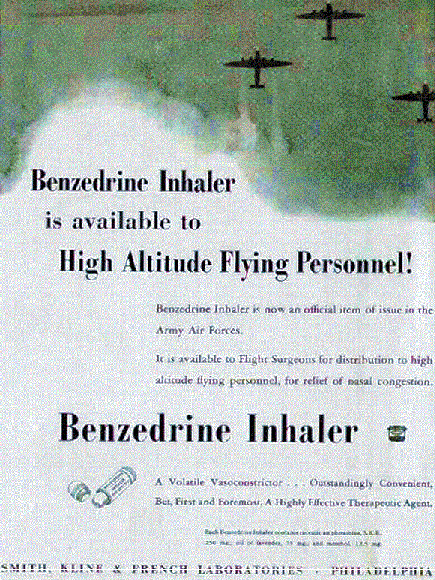

A key satire of this came in 1932 with what is now the archetypal drug dystopia, Aldus Huxley’s Brave New World. This was right as real-life drug development was triggering overlaps between medication, performance enhancement and eventually recreation. Benzedrine was sold as a mass-market decongestant from 1933 and had a great many other medical uses, but – containing amphetamine – it also became an energising pick-me-up for housewives and bomber pilots alike. The warring totalitarianisms of the time, and new concepts of thought-control, spawned fictional drugs like the truth-serum of Karin Boye’s Kallocain, published in 1940.

With the 1950s came a golden age of psychopharmacology and a string of breakthroughs including antipsychotics and antidepressants. It was thought by some that chlorpromazine, the first antipsychotic, would hail the end of psychosis altogether. This utopianism was seen in another golden age of the time, that of science fiction, portraying an organised and self-made humanity that journeyed outwards on galactic adventures. Surprisingly, or perhaps not, this optimism coincided with a lessening of fictional drugs.

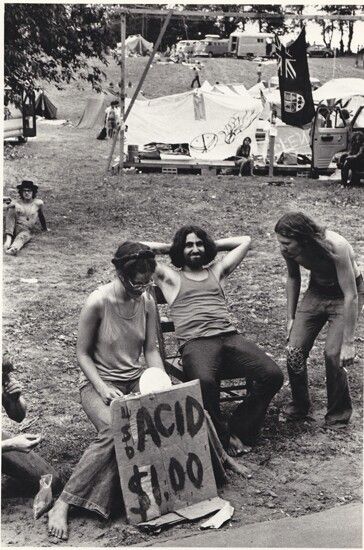

But with the 1960s came an explosion of real-world recreational drugs and wider use of psychotherapy. The frenetic self-obsession of Benzedrine and Freud gave way to the societal deprogramming of LSD and Laing.

The counterculture was dissatisfied with what it saw as the tangle of ideologies and assumptions that had ultimately resulted in two world wars, the Cold War and an ongoing Vietnam War. Many identified this as the western tradition, so eastern philosophies were explored in its place, as well as a renewed interest in indigenous American beliefs and practices. It was here that the ritual use of psychoactives (a relatively global feature of civilisation, but enduring in the Americas) was appropriated and its traditional elements largely stripped away, leaving a goal both simple and not: the expansion of consciousness.

Where the counterculture accepted Freud’s model of the mind and its focus on the ego, as well as the practice of psychological self-improvement that had arisen from it, some saw the ‘solution’ to the ego as its destruction. The method was a joint salvo of basement-brewed chemicals and unguided readings of the Upanishads and Tibetan Book of the Dead. Self-improvement was good; self-obliteration was better.

This was at least the idea. The 1970s saw the gradual redress to hippy utopianism, which in many ways changed society for the better but at its most extreme was arguably no less hubristic than the Buck-Rogers fantasies of the previous generation. Fiction of course relished any emergence of addiction, destroyed minds and obliterated lives – if not selves. Paranoia crept in, with tales of infernal doom-spirals and clandestine government drug trials.

As the 1980s dawned, the last vestiges of the counterculture were neutered by ad agencies and Silicon Valley, and in came the spectre of the corporation. Mind-melters were no longer picked gaily from meadows or brewed by nouveau shamans but printed in endless blister packs from stirring pharmaceutical beasts. Brave New World – written half a century ahead of its time – had come to pass3Although it should be noted that perhaps the most emblematic novel of not just drug utopianism (this is in any case a narrow field) but wider hippy utopianism to have emerged in the intervening period, and which looking back seems to embody all of the self-delusions and failures of the countercultural project, was also written by Huxley: 1962’s Island..

My brain made me do it

It’s perhaps too soon to characterise how recent generations of fictional drugs have responded to our age. Some have claimed that, where previous drugs sought to give forbidden knowledge, expanded consciousness, special abilities, those of recent decades have addressed our era’s floods of information by seeking to remove properties, certain fears or painful memories or just the noise of it all, not so we may then do more but merely so we can be at peace.

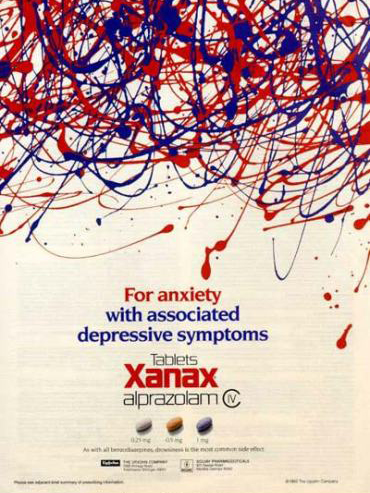

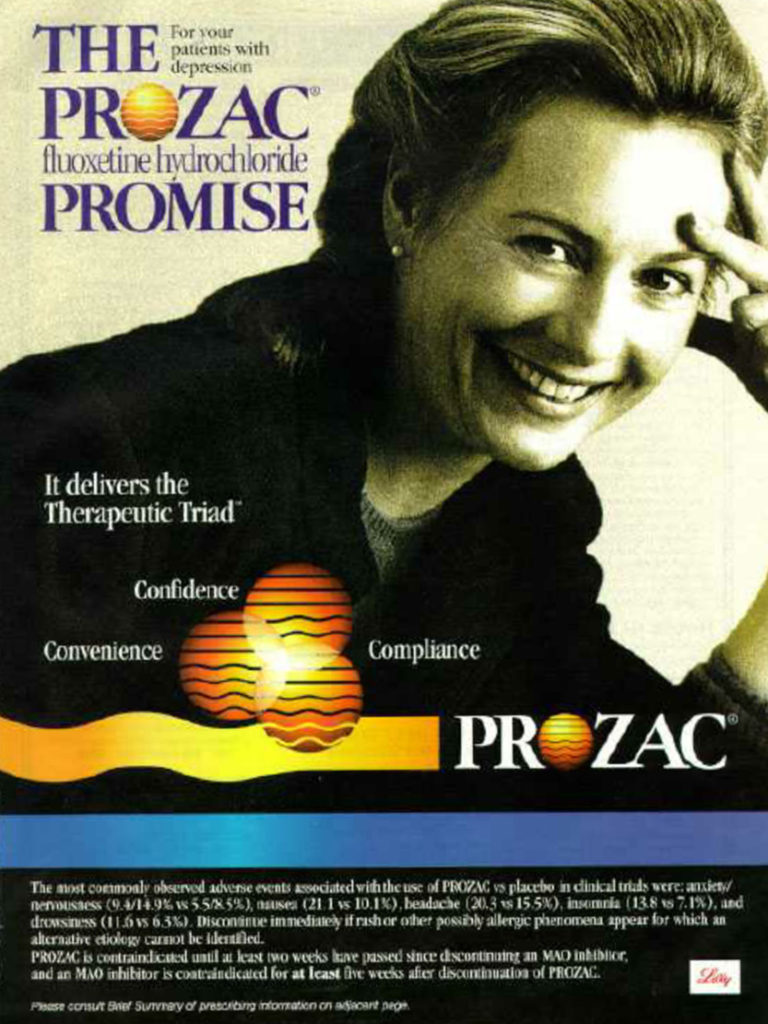

This feels an apt historicisation of the prescription drugs that became so embedded in pop culture and in particular music, Prozac in the 1990s and Xanax in the 2010s, and aligns with the stories we currently like telling of ourselves: that the vast ocean of information and our reality-shifting means of swimming it – digital mass culture and social media – are actually a huge burden that previous generations didn’t have to deal with and can’t understand. To this view we are traumatised and fabulous individuals who must, against the odds, live our truths.

But drugs that deaden and excise have been around in reality (like Valium) and fiction (like Dylar) long before the online world, and fictional drugs are now as diverse as ever, drawing on and replicating all previous modes. Perhaps that is itself the theme of our online age: that culture is less a menu of current habits, as it has been, but a reference archive of genres, diverse materials with which to construct narratives, something for everyone yet nothing entirely new.

Another shift in fictional drugs may require a new model of the mind to respond to. The model of chemical interactions has had great use scientifically, but so do many models that are later overhauled or replaced. It may be superseded by some as-yet-conceived view on the substance and location of the mind, triggered by some technological change that’s equally unconceived, or currently just a hunch and some seed funding.

For now we remain inside the model, not least because it’s a perverse comfort to think of ourselves as chemistry sets. To believe we can make interventions in a plan that no longer satisfies is something that enables us to feel at once blithely powerless (because certain deficiencies may be part of our ‘natural’ make-up and so not our ‘fault’) and divinely powerful (because we may eradicate them – with drugs!). The result is an ambiguous notion of personal responsibility that’s freeing for some and crippling for others. The only clear winner is the pharmaceutical industry.

My brain made me do it, we might say, but I should have taken something to stop it happening.

This may seem like a feature of the modern mind, of we secular tinkerers presuming to improve the handiwork of mere nature. But classical Greeks were playthings of the gods, as they saw it, and Daoists yielded to the ebbings of the Way and astrologers from the Andes to the Indus perceived themselves subjects to cosmic movements – while at the same time they sought to outfox the fates and channel the flows and avert their own predictions, to redirect that which was inevitable.

The creation of drugs, real and fictional, is one way of condensing this very old question, one that lies equally at the root of storytelling: the question of what we can change and what we cannot.

A is for…

Adrenochrome

Origin: Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas. a novel by Hunter S Thompson (1971). Harvested from the adrenal gland of a living human, therefore produced only in horrific circumstances.

Appearance: Clear liquid inside a small brown bottle in your attorney’s shaving kit.

Dose: “A little tiny taste,” he advises.

Effects: It apparently ‘makes mescaline seem like ginger beer’, so has the dissociative, depersonalising and stimulant properties of mescaline but presumably times ten.

Adverse effects: Hyperkinesia, hypersensitivity, a near-violent need to hear a story come to its conclusion (cruelly improbable in the context) and ultimately blackout.

Class: Drugs that are like existing drugs but more so. Sounds unimaginative but works oddly well for psychedelics, which in literary terms are often evoked by sidelong strangeness rather than directly. If the writer has the chops to describe the indescribable (or somehow to demarcate the space in which the experience occurs) then it can work. Thompson works it.

Notes: An adrenal compound called adrenochrome does exist and was hypothesised to have hallucinogenic properties and a link to schizophrenia. Aldus Huxley mentions it in 1954’s seminal trip-diary The Doors of Perception, noting its seeming ability to ‘produce many of the symptoms observed in mescalin intoxication’ and that ‘the sleuths – biochemists , psychiatrists, psychologists – are on the trail’. Studies occurred across the ’50s and ’60s, and from these Thompson may have come across it and adapted it to his ends. But none of the initial hypotheses panned out. It may be through the undulations of science, therefore, rather than any intentions of Thompson, that the adrenochrome of Fear and Loathing slipped from hypothesis and into fiction4That is, for most people. More recently the debunked idea of adrenochrome working as a recreational drug has provided an occult subplot for conspiracy theories like QAnon, in which adrenochrome is harvested from children by the global elite for use in satanic ritual. One wonders what Thompson, who followed Fear and Loathing with Fear and Loathing on the Campaign Trail ’72, an acerbic account of Richard Nixon’s re-election campaign, would have made of QAnon’s role in the attempted re-election of Donald Trump, given that the fictional drug at the heart of the theory may only be known at all because of Thompson’s novel….

B is for…

Black meat

Origin: Naked Lunch. Novel by William Burroughs (1959). From the meat of the giant aquatic Brazilian centipede.

Appearance: Black powder in a bottle. Smells like tainted cheese.

Effects: Perhaps reveals a secretive stratum of factions and manipulators that vie for control of the narcotic supply, political influence and ultimately of lived reality.

Adverse effects: Perhaps causes hallucinations of a secretive stratum of factions and manipulators that vie for control of the narcotic supply, political influence and ultimately of lived reality.

Class: Fictional drugs that, even within the context of their fiction, do not exist. This is raised both in the book and film, but it’s only in Cronenberg’s 1991 adaptation, a much more biographical sort of meta-take on the novel (which is deliberately incoherent), that the black meat becomes more clearly a stand-in for other things that do exist. In this sense it could arguably be a subcategory of metaphorical drugs (see gerin oil), operating as a cover for Burroughs’s once-repressed sexuality, which was finding (highly, highly problematic) expression in Tangier5On which it seems Cronenberg doesn’t pull any punches, especially considering Burroughs himself was pottering around on set. But the writer’s letters and more biographical books make clear that he was up to some exceptionally horrendous things in the freedom of Interzone – or the semi-lawless ‘international zone’ that Tangier was at the time. These things are seldom alluded to when it comes to Burroughs., or just for heroin, which was perhaps the chemical fuel for the whole book’s creation and which through its addictiveness served to recompose Burroughs’s reality into the factions that would and would not enable him to get more – like black meat’s ability to ‘reveal’ the conspirators of Interzone.

Notes: In the film, black meat is presented initially as a remedy for the addictive effects of bug powder, a pesticide that main character and Burroughs alias William Lee – an exterminator – injects to produce what his wife calls a ‘literary high’6‘A Kafka high,’ she continues, ‘it makes you feel like a bug.’ This is a clear reference to Franz Kafka’s ‘Metamorphosis’ and its protagonist’s transformation into an insect. The body-horror imagery of this will of course have been appealing to Cronenberg, but the influence of Kafka on Burroughs seems significant, in particular The Trial and its labyrinth of nonsensical workplace and legal procedures ensnaring and destroying its hero. This rejection of the organised, rational world as malign and false could be seen as the touchpaper for what Burroughs went on to do with his fractured narratives and the well-known cut-up technique. In Cronenberg’s Naked Lunch, Lee interjects as his friends (the not-quite-Kerouac and not-quite-Ginsburg) discuss the purpose of art to state, deadly serious, that it is to ‘Exterminate all rationality’.. Burroughs had in 1956 been introduced to apomorphine to alleviate his heroin addiction, which he claimed had ‘cured’ him. But apomorphine has never been widely accepted as an effective treatment, plus he had in the meantime become addicted to paregoric, a tincture of opium. This triad of drugs may be the basis for bug powder’s addition to the film, with black meat offered (by an experimental psychiatrist, as Burroughs was offered apomorphine by psychiatrist John Yerbury Dent) as a cure to bug powder addiction but ends up much stranger, darker and no less addictive7It could also be read that addiction to bug powder being cured by black meat is simply a malicious hallucination of the original drug, which Lee never kicks at all. One can imagine Burroughs peering at his bottle of paregoric as it wove its molecular threads through his body and wondering the same thing about that drug, apomorphine and everything else he had taken since he stopped heroin. The adversary here would not be any particular drug, real or made-up, but addiction itself, and its fictive, even literary means of dominating the mind.

C is for…

Cake

Origin: Brass Eye, television show by Chris Morris (1997). But more specifically Prague.

Appearance: A luminous yellow pill, approximately seven inches in diameter.

Alternative street names: Rustledust, chronic Basildon donuts, Joss Ackland’s spunky backpack, bromacide, argue barmies.

Effects: A bisturbile chranabolic amphetamoid, cake makes a second feel like a month and is capable of extending a single sonic blip into a complex noise-symphony. Turns rats into space hoppers.

Adverse effects: Nonsensically addictive. Causes children to cry all the water out of their bodies – and at the same time, mysteriously, significant water retention. Death by vomiting.

Class: Made-up drugs. Made up of chemicals, that is, but also lies. In the case of cake this lie was to trick various celebrities into speaking about its ridiculous effects and origins, and in so doing hold a mirror to ‘90s tabloid fears over ‘party drugs’ such as MDMA. See: bananadine (The Anarchist Cookbook), claimed in 1967 to be a psychedelic extracted from banana peels, the invention of which was intended to make legislators reconsider the sense of banning naturally occurring psychoactives. In practice it led to eager psychonauts trying in vain to get loopy off bananas. Also: satirical drugs. See: money (South Park), which is liquidised and injected as a cure for HIV (reflecting the cost and inequalities of HIV treatment).

Notes: In 1997, Member of Parliament David Amess raised the horrors of cake as a question in the House of Commons. This is amusing, but he was receptive to the hoax because he was campaigning against recreational drug use following the death of a fifteen-year-old constituent from an MDMA overdose in 1995. The lesson is perhaps that, while legislators may feel they have only so much time in the day for experts, they should still see more experts.

D is for…

Dylar

Origin: White Noise, a novel by Don Delillo (1985).

Appearance: Saucer-shaped tablets in an amber bottle of lightweight plastic.

Dose: One every three days.

Effects: A cutting-edge drug delivery system, Dylar is encased in a polymer membrane that releases its medications at a carefully controlled rate into the gastrointestinal tract (‘slowly, gradually, precisely’). Removes fear of death.

Adverse effects: Memory loss, frequent and prolonged. Inability to distinguish words from things.

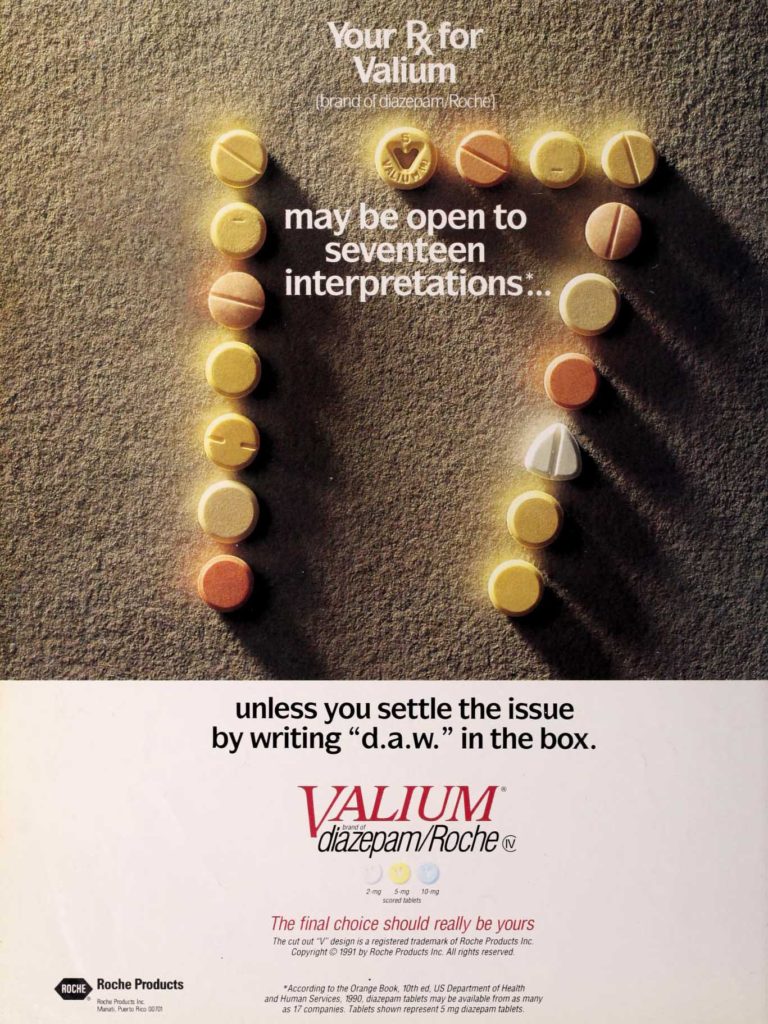

Class: Anxiolytics. In the decade White Noise was written, many countries were introducing strict regulation on the use of anti-anxiety medications, in particular benzodiazepines such as Valium. That is, except the United States, where the use of such drugs became more entrenched and normalised than anywhere else8Valium in particular diminished in use as alternatives entered the market in the early ’80s and Hoffmann-La Roche’s patent on the drug expired in 1985. White Noise actually caught the relative end of anxiolytics as the dominant prescription drug in the US, with SSRIs (selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, a form of antidepressant) emerging in the late ’80s and diagnoses for the same amorphous bundle of symptoms switching significantly from ‘anxiety’ to ‘depression’. There were of course clinical reasons for this, but it was also due to the negative public profile of benzodiazepines and a growing stigma in taking them, as well as (in a very White Noise-ian way) there simply being new products on the market, new ad campaigns, and so new diagnoses.. Dylar’s USP is that it’s formulated to target a particular anxiety: the fear of death, which in White Noise is presented as an underlying anxiety to the emptiness of consumerism. But Dylar isn’t a replacement to the era’s emergent media overload – of information, of visual stimulus (in the form of abundant TV shows, hypnotic advertisements) and things (endless consumer goods purchased as a result of those ads); it’s a sort of companion drug, a sedative that allows one to disappear into those things, lost but content.

Notes: The body of course has its own defence mechanisms when it comes to overload, and Dylar’s side effects mirror these: forgetfulness, confusion over words and facts, and the characters in White Noise are very frequently doing this. One ‘thought Dylar was an island in the Persian Gulf, one of those oil terminals crucial to the survival of the West’. Dylar has exactly this role: it suggests that self-delusion, the power to mythologise, to remake ourselves according to what we buy and in this way secure immortality, has been the real key to the survival of the west. Or at least to its endurance so far. This hollowness makes it ultimately a failure on its own terms: it endures but for no other reason than to sit and watch stories and buy.

E is for…

Ethical birth control pills

Origin: ‘Welcome to the Monkey House’, a short story by Kurt Vonnegut (1968). Developed originally to stop monkeys committing obscene acts in zoos, the drug was found to have similarly chastening effects on humans.

Dose: Three per day.

Effects: Numbness from the waist down, loss of all libido.

Adverse effects: Blue urine.

Class: Population-control drugs. See: BlyssPluss (Oryx and Crake), an all-rounder that fills you with energy, happiness, protection from sexually transmitted disease and is even anti-ageing, but also secretly makes you sterile; and all vaccinations (conspiracy theorists, various), which may or may not contain immunogens but definitely contain hidden sterilising agents for the purpose of eliminating particular groups, or all groups. This is just one of the many uses of fictional vaccines, which are among the most versatile of fictional drugs.

Notes: In the ’60s or ’70s, anxieties of global overpopulation went mainstream through writers like Paul Ehrlich in his popular and controversial The Population Bomb. Older, Malthusian ideas of a packed planet of depleting resources were elaborated with systems theory, population dynamics and models of ecological collapse, and this soon filtered through to literature and film, from Make Room! Make Room! to Logan’s Run. It’s the basis for ‘Welcome to the Monkey House’, but its drug stems from another, connected theme of the time: reproductive control and sexual liberation. The contraceptive pill had emerged to give women a new degree of sexual autonomy, and with it came a relaxation of attitudes to sex9Yet, while the story satirises the conservative fear of these attitudes, Vonnegut at the same time employs the notion that a woman’s ‘frigidity’ may be ‘cured’ by sexual assault. For this the story is somewhat infamous, and perhaps shows that within the right-on positions of a given historical moment can always lurk much older and darker assumptions. But such control fired the imaginations of many: if such a thing could be wielded by the individual then it could be wielded by the state, which might consider it a ‘solution’ to overpopulation. Of course, forced sterilisation far predates this as a concept and practice, including in the United States, but the discreet and everyday nature of drugs meant far more clandestine methods could be imagined, including those in which the population would be in some way tricked or ‘convinced’ into self-administering its own sterility10As birth rates came to slow, due in part to socioeconomic shifts and forms of urbanisation unanticipated in the ’60s, overpopulation diminished as an issue in academia and the public consciousness. In 1994 the United Nations officially renounced population control as one of its aims (it’s of course striking to us now that it ever was one). But there are many for whom the idea of population-reduction through state-controlled reproduction remains real, along with the drugs used to carry it out. These views, now increasing again in the form of anti-vaxxers and others, and in part merged with the sci-fi stories they earlier spawned, are a hangover from a previous era.. ‘Welcome to the Monkey House’ plays on this to describe a conservative older generation using a drug to curb procreation by ending sexual desire.

F is for…

Fluid karma

Origin: Notoriously inscrutable 2000s-fest Southland Tales, written and directed by Richard Kelly (2006). Or rather an organic compound found beneath the Earth’s mantle which can be used to create an electromagnetic energy field that’s also called fluid karma and works by quantum entanglement to generate a new global power source but which may also tear a rift in space-time.

Appearance: A liquid in a range of colours and corresponding strengths. If taken as a drug, rather than using it to cure civilisation’s energy woes, then it’s via the classic sci-fi auto-syringe.

Effects: Biblical visions, telepathy, ability to see through time.

Adverse effects: Auditory hallucinations of Killers songs.

Class: Drugs whose effects are the by-product of something actually useful. See: Ephemerol (Scanners), developed as a safe sedative for pregnant women, it ends up giving their unborn children the ability to control the brain physiology of others, enabling them eventually to control minds and explode heads. Another of several Cronenburgian mentions on this list.

G is for…

Gerin oil

Origin: ‘Gerin Oil’, an article in Free Inquiry by Richard Dawkins.

Appearance: Dog collars, hassocks, little chapels on hills, bar mitzvahs, kids running along alleys as the muezzin resounds.

Effects: In low doses it is a ‘lubricant for social occasions such as marriages, funerals and state ceremonies’, providing that ambient glow of community and meaning.

Adverse effects: Autolocutory disorder, manic stereotypy, and ultimately terrorism, the hunting and burning of witches, assorted massacres.

Class: Metaphorical drugs. We can only assume that one as on-the-nose as gerin oil must be taken nasally. See: red pill / blue pill (The Matrix), the latter meaning a return to falsehood while the former permits the user to know reality11The red pill is also in 1990’s Total Recall, again symbolising the choice for reality and again using the dream-logic (or potential dream-logic, in Total Recall’s case) of its setting to both symbolise and actually realise that choice. The red pill / blue pill are not in ‘We Can Remember it for You Wholesale’, the Philip K Dick story from which Total Recall came. Crushingly I can’t find anything on Paul Verhoeven’s inspiration for its addition to the film.. In Douglas Hofstadter’s genre-bending 1979 masterpiece Gödel, Escher, Bach there are vials of blue and red liquid, a ‘pushing-potion’ to enter the false worlds of paintings and ‘popping-tonic’ to return to reality. Hofstader was strongly influenced by Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland and the vials echo the potion and cake that shrink and grow Alice respectively. The Matrix opens with its protagonist being told to follow a white rabbit, one of its many Wonderland references.

Notes: As every sixteen-year-old social scientist knows, religion is the opiate of the masses and this is a thing that Karl Marx said12Marx also said, much more beautifully and interestingly, that religion is ‘the heart of a heartless world’. If it is a component of a world that does not have this component, then this component exists outside of the world and therefore not at all, yet the syntax of the phrase – it is the heart – demands its existence. It’s a paradox, and one that doesn’t decry religion, as many presume Marx to have done generally, but feels sad, like he’s mourning someone who was never born.. Dawkins takes it very literally in making his point, but it’s effective. A metaphorical take-down can sometimes stumble in its being an ‘argument from analogy’, whereby agreed similarities between two things are used to infer further similarities that have not been observed. This is standard to human perception, but a problem arises where the agreed similarities are in fact the limit of what can be compared and inferences beyond are false. In other words the analogy sounds better than it truly works. But gerin oil is powerful because the effects of both drugs and religion can be described in biochemical terms.

H is for…

Hormone K

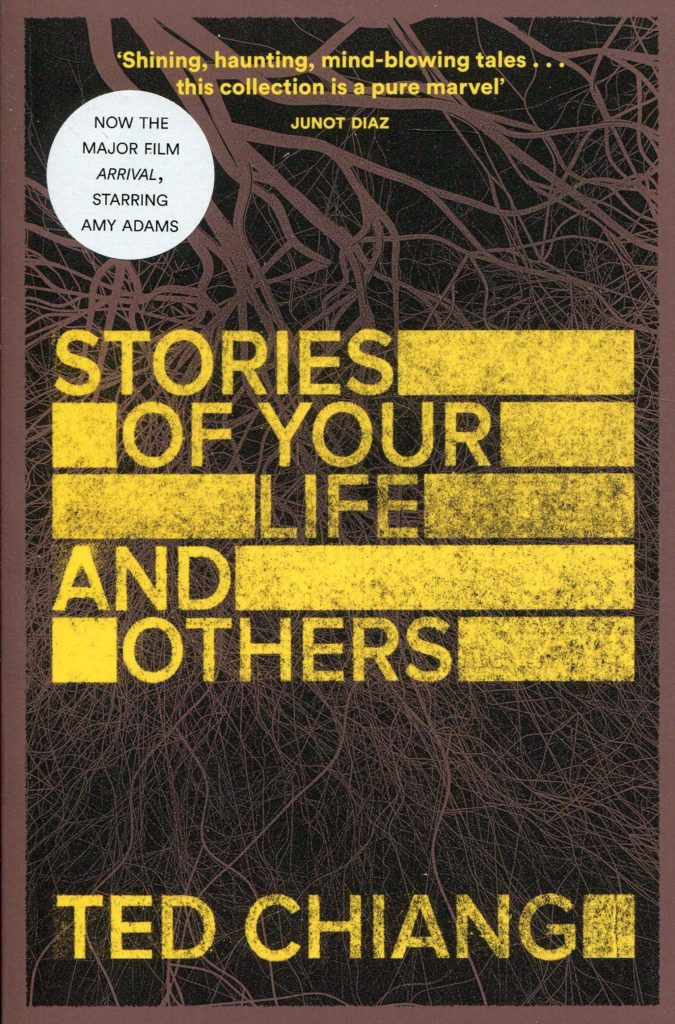

Origin: ‘Understand’, a short story by Ted Chiang (1991). The nature and origin of the hormone are not explained.

Appearance: Liquid in an ampule.

Dose: Two injections to rebuild some neurons; three to get pretty good at multitasking; four for your self-awareness to become itself self-aware.

Effects: Generates neurons in proportion to the number of neurons previously lost. On severely brain-damaged patients this can result in hyper intelligence and acute body-control, to the extent that one can extrapolate the thoughts of others through their pheromones and even manipulate their brain-chemistry through calculated somatic excretions.

Adverse effects: Becoming quite aloof. Also nightmares.

Class: Nootropics, AKA smart drugs. The schema is simple and essentially that of Icarus: the protagonist is offered a novel but untested power by some Daedalian science-guy and it goes well as the protagonist climbs ever higher – but then is zapped from the sky by cosmic forces, displeased at this perversion of nature’s order. An occasional variant on the Icarus tale, though, is where this perils-of-science trope is used to make the protagonist into antagonist, as in ‘Understand’ where the main character more or less becomes a supervillain. Any story that attempts this is itself perverting a very old order. Perhaps just as bold is the smart-drug narrative’s need to have exceptional intelligence described in convincing terms; a writer undertaking this is generally asking for trouble. Ted Chiang is one of very few who can pull it off. See: MDT-48 (The Dark Fields), which became NZT-48 in Limitless and shares the high-level pattern-recognition of hormone K but is more conventionally addictive; and formula 5 (The Lawnmower Man), which offers psychokineses and telepathy as well as another of the smart-drug antagonist’s favourite desires: to transcend the body’s fleshy cage and become a cackling CGI loon.

I is for…

Iocane

Origin: The Princess Bride, a novel by William Goldman (1973). But really it’s from Australia.

Appearance: Powder. Odourless, colourless, dissolves instantly in water.

Dose: A bit.

Effects: Death.

Adverse effects: Death.

Class: Murder drugs. No literary give-and-take, no allusion or metaphor, just death. The only variable is how funny the method is. See: smilex (Batman), a lethal poison formulated by the Joker to leave a wide grin on the victim’s face; dust of death (Marvel Comics), Red Skull’s poison that makes the victim’s head turn into a red skull; bloat (Pyramids), used by Discworld assassins to make the victim’s cells instantly try to swell to two thousand times their normal size, a process ‘invariably fatal, and very loud’.

Notes: In The Princess Bride, the hero Westley takes iocane but is unaffected because he has deliberately built immunity to it over time. In reality this is called mithridatism, and while there are apparently snake handlers who swear by it, it’s generally not seen as reliable for use with lethal poisons. And yes iocane is a poison, but the difference between a drug and a poison is largely one of intent, and they blur in many instances. Iocane certainly isn’t a recreational drug (or it would be short recreation, any case) but there are cases of substances intended as poisons being used recreationally, like the venom of the Sonoran Desert toad.

J is for…

Jekyll’s potion

Origin: Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde, a novella by Robert Louis Stevenson (1886). A garden laboratory behind a respectable London house. Made from some kind of ‘blood-red liquor’ and a white crystalline salt, unspecified but available from your local chemist.

Appearance: The vintage mad-scientist brew, multi-hued and frothing.

Effects: A ‘solution of the bonds of obligation’, it removes all barriers from pursuing material pleasures.

Adverse effects: The repercussions of pursuing material pleasures. Also physical deformity.

Class: Temptation drugs. Jekyll’s desire is not simply for the drug, or even for the things Hyde will get up to once Jekyll has taken it, but for the part of himself that is ordinarily hidden away, that is Hyde. Such drugs are a test of temperance, and the story – inherently moralistic – lies in the test’s failure.

Notes: The drug facilitates the emergence Hyde but in Jekyll’s view is itself ‘neither diabolical nor divine’; it is a neutral revealer of what is already the case, similarly to Griffin’s formula (technically not a drug) in HG Wells’s The Invisible Man (1897). As Victorian Britain’s intense conservatism collided with the era’s wild new sciences, the question of humanity’s ‘essential nature’ and the degree to which it is God-given or malleable gained greater intensity. The success of a story like Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde is in its positioning of the drug as a symbol of both scientific discovery and the trial of life in a Christian worldview, enabling it to ask the question of ‘essential nature’ while still operating as essentially a tale of failed abstinence13It’s in this that the story makes itself what Stevenson called a ‘bogey tale’, or what we call horror, and seen in this light it is more straightforwardly conservative in values, like most horror before and since. But it is – like most conservatisms before and since – dissonant in nature, at once making prohibitions and relishing what is prohibited. This is mirrored in Jekyll, his piety annulled as he returns hungrily to Hyde. In this there is something fundamentally Victorian about nearly the whole horror genre, even today. And while there are still some who believe horror and sci-fi incompatible, the genres align well in their obsessions with what can and cannot be known, what should and should not be known.. The more ‘religiously minded’ reader of the time could therefore engage with the question without feeling they were in some kind of unholy territory.

K is for…

Kallocain

Origin: Kallocain, a novel by Karin Boye (1940).

Appearance: Pale green liquid

Dose: Small amount via intravenous injection.

Effects: Sense of well-being. Speaking freely.

Adverse effects: Execution for thought crime.

Class: Truth drugs. In their broadest sense these aren’t fictional, with kallocain likely inspired by scopolamine and sodium thiopental, which entered use in the 1920s. But really these drugs don’t have the efficiency or reliability demanded by the truth drugs of storytelling; they work by lowering inhibitions, so their results are as varied those of other inhibition-lowering drugs, like alcohol. See: veritaserum (Harry Potter series).

Notes: While Kallocain bears lots of similarities to George Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four, such as the totalitarian Worldstate and the forcible extraction of thought crimes, and was published eight years before Orwell’s novel, Kallocain didn’t appear in English until 18 years after. Rather than one influencing the other, likely they were both influenced by Yevgeny Zamyatin’s We – as, possibly, was Aldus Huxley’s Brave New World. (Although Huxley claimed he’d never heard of We. Orwell said he was lying.)

L is for…

Ladder

Origin: Jacob’s Ladder, a film directed by Adrian Lyne (1990). Also a US military lab in Saigon.

Dose: An infinitesimal drop in the food supply.

Effects: Heightened aggression, intended to increase combat effectiveness.

Adverse effects: Aggression that is directionless and uncontrollable, massively decreasing combat effectiveness.

Class: Combat drugs. From the soldiers of ancient Greece and Rome taking alcohol to the Wehrmacht dolling out amphetamines, drugs have long been a part of warfare14There are also speculations on the use of mushrooms before battle, such as amanita muscaria by Zulu warriors, various tribes of eastern Siberia and more famously by Vikings, but these are all contested. Another theory suggests that Viking berserkers’ trance-like ferocity was induced by henbane, a poisonous psychoactive on which German scientist Michael Schenck (related by Alexander Kuklin, related by Wikipedia) said he was flung into ‘a witches’ cauldron of madness. Above my head water was flowing, dark and blood-red. The sky was filled with herds of animals. Fluid, formless creatures emerged from the darkness.’ Sounds about right.. The ‘performance enhancement’ may be the lessening of pain or increasing of physical skill, but a common theme of these drugs seems to be emotional detachment and the deadening of thoughts that may hinder the grizzly task at hand. See: betathanatine (Altered Carbon), created to research near-death experiences but its removal of emotional response makes it ideal for soldiers; slaught (Warhammer 40,000 universe) fantastically named bloodlust-heightener; and valkyr (Max Payne), failed combat stimulant turned chaos-unleashing street drug (see crimewave drugs under Zyme).

Notes: The postscript to Jacob’s Ladder indicates that a drug called ‘BZ’ – 3-Quinuclidinyl benzilate – was inspiration for ladder15The director later said there is nothing to suggest BZ was used on human test subjects, which makes it an odd thing to put in the postscript to his film, unless this was an understanding he came to only later. Either way, a 2012 a lawsuit (brought by a group of former soldiers against the US government relating to drug experiments allegedly performed on them – not dissimilar to the plot of Jacob’s Ladder) led to the release of a US government document that shows BZ’s solubility in human blood, which it would be difficult to determine without human testing.. BZ research was likely part of the CIA’s wider MK-Ultra programme, which spent much of its focus between 1953 and 1964 on LSD as a possible truth and mind-control drug (see truth drugs under Kallocain), testing on many human subjects before eventually LSD was deemed too unpredictable in effects and instead engineering their own ‘super-hallucinogens’, among which was BZ16BZ was modelled on atropine, the active ingredient of Datura, a plant long used in Central American shamanic practice. erowid.org notes its effects as ‘delirium, extreme disorientation, and realistic hallucinations’ and can last two to three days, putting it firmly in the ‘heavy shit’ category of psychoactives.. We can only speculate as to its intended use, whether another truth drug, a combat stimulant or even chemical weapon, but it’s easy to see why revelations about such experiments played a part in how fictional drugs and drug culture itself had shifted by the late ’70s. The utopian sheen had come off.

M is for…

Melange

Origin: Dune, a novel by Frank Herbert (1965). Produced on the desert planet Arrakis from the fungal excretions of baby sandworms.

Appearance: Liquid. Taken orally and never tastes the same twice, yet somehow smells consistently of cinnamon.

Alternative street names: Spice.

Effects: Increased mental acuity, radical life extension and, in some users, prescience. In Dune, these users can become navigators, who use melange to perceive the safest possible courses that a spaceship might take when ‘folding’ space to travel vast distances instantaneously.

Adverse effects: Light use causes eye discolouration; heavy use turns the user into a massive aquatic slug17This was seemingly a flourish of the 1984 David Lynch film and from there made its way into subsequent novels.. Highly addictive.

Class: MacGuffin drugs. It’s said that he who controls the spice, controls the universe – so everyone wants the spice, so there’s your dramatic impetus and story. Spice being the key to space travel makes it very important in the Dune universe, but it actually features relatively little, which is a common trait of MacGuffins.

Notes: While Dune is of course science fiction, spice and space-folding is one the very few science-y things in the story, which in style is more like a medieval romance or religious epic. Dune’s lore is embedded in the mystical ephemera of ‘60s counterculture, such as its religious admixture (Herbert notes ‘Mahayana Christianity, Zensunni Catholicism and Buddislamic traditions’ in Dune’s glossary) and use of indigenous American psychedelic ritual (Mexican mushroom cults inspired the order of the Bene Gesserit). Herbert was partial to psilocybin, and the inspiration for expanding one’s consciousness (and empire) across the universe through the use of naturally occurring drugs isn’t hard to guess.

N is for…

Neuroin

Origin: Minority Report, a film directed by Steven Spielberg (2002).

Appearance: Liquid aeorsolised by a fun-looking inhaler.

Alternative street names: Clarity.

Dose: A single honk.

Effects: Euphoria, analgesia. In the case of babies born to heavy users it can cause an ability in the baby to see the future, or one of several futures.

Adverse effects: Severe addiction. Untidiness.

Class: Demon drugs. That is, they give characters demons to make them interesting. In the film, the main character is a straight-laced and dull Tom Cruise-type (luckily played by Tom Cruise), but who has a private addiction brought about by the earlier death of his son. It’s by-the-numbers and undeniably effective. Drug-taking can make for a very direct visual cue of ‘weakness’ and the desire to get outside of oneself: of ‘turmoil’.

Notes: The Philip K Dick story from which the film is adapted, ‘The Minority Report’, actually does not contain neuroin or any drugs at all18This seems strange considering that Dick’s stories are known to be rife with them. But perhaps less so than one might think, if Minority Report and Total Recall (see note 19), in which the drugs are additions of the screenplays, are anything to go by.. Still, neuroin being an addictive and debilitating drug that in certain circumstances grants special knowledge is a very Dickian thing. As a longtime user who at points suffered paranoia, he knew the oscillating self-delusions and self-awareness that can be characteristic of addiction. It’s fortunate for us that as a writer he was able to use the latter to elucidate the former. And, perhaps because of this, even those of his stories which don’t contain drugs still lend themselves to the sense of narcotic influence because they are so frequently about the suspicion of malign forces and the questioning of reality. They feel like drug narratives even when they’re as clean as Dick later became, or mostly became. It’s this (combined with the dealer’s duffel bag of drugs that he did invent19Philip K Dick pharmacopoeia

Can-D and Chew-Z. From The Three Stigmata of Palmer Eldritch, Can-D is a plant-based hallucinogen that allows ingesters to sort of astrally project – together – into doll-like props and live more agreeable lives elsewhere. Chew-Z emerges as a competitor drug that doesn’t require the props at all. What seems indicated but unexplored in the novel, though, and what may be the most interesting characteristics of any fictional drug that I’ve read anywhere, is that this shared reality may not be shared at all, and the astral projection may be no such thing. Two people can enter and leave an experience they believe profoundly shared, and that they have gone to another world they could not otherwise enter, yet in truth they were never there or even with each other, and don’t have any conceptual means of confirming it. (The irony is that, thinking about it, this may have not been indicated in the novel at all and I’m misremembering. I can’t find it in any synopsis. In other words I may have invented a shared reality between myself and the novel that never in fact happened.)

Hardovax. From Galactic Pot-Healer, a no-frills pill to treat erectile dysfunction. (When one considers this, The Simpsons (see footnote under Repressitol), multiple entries for Saturday Night Live, and others, it’s amazing how many fictional drugs relate to erectile dysfunction.)

JJ-180. From Now Wait for Last Year, a lethal and highly addictive pill that also induces time travel. Similarly to Can-D’s gift of shared reality and traversing of distance, a quality of Dickian drugs is to make the experience of real-drug taking itself real.

KR-3. From Flow my Tears, the Policeman Said, an experimental drug that appears to break down the subjective perception of space as other drugs do of time, resulting in a kind of spatial non-linearity in which ‘competing spatial corridors are opened’ and ‘a whole new universe appears to the brain to be in the process of creation’.

Substance D. From A Scanner Darkly, an amphetamine-like psychoactive street-drug in one of Dick’s most autobiographical novels, and which marked a turning point in his attitude towards and representation of drugs, namely that they are wholly malign, deceptive and ultimately damage one’s mind. Substance D is not produced by a nefarious government but a hippy commune via the processing of a particular flower. It therefore does indicate a move beyond the antagonist and mind-controller being some entity of the state, as was a cornerstone of the countercultural sensibility and the post-Golden Age sci-fi of which Dick had been one of the principal architects, perhaps the foremost, and to a scepticism of the countercultural project itself. This makes sense, given the novel’s publication date of 1977. What’s interesting is that this puts Dick at the forefront of not one but two of the major shifts in fictional drug creation, and perhaps that its course over a sizable part of the late twentieth century was tied to the course of his own personal drug use.) that makes him pre-eminent in the whole discipline, the Odysseus of mythopharmacology.

O is for…

Obecalp

Origin: ER episode ‘Shifts Happen’ (2003). Okay, obecalp didn’t originate in hospital drama ER, but it’s the earliest use of this fictional drug in a fictional context that I’m aware of. It was an Australian doctor who in 1998 coined the term by inverting ‘placebo’.

Appearance: Plausible-looking pill in a plausible-looking container.

Effects: Potential alleviation of symptoms modulated by the brain, such as pain, anxiety, fatigue, nausea.

Adverse effects: As expectations of positive effects can appear to manifest, it’s suggested that so can expectations of side effects, known as the ‘nocebo effect’.

Class: Fictional drugs that are also real. Obecalp is fictional in that there is of course no chemical intervention occurring, yet the placebo effect is clinically observed in improving how a patient feels, while not curing them. Belief, expectation, narrative – these things can change the chemical balance of the brain, and the nocebo effect fits this. The fall-and-rise dynamic of stories transposes well into the dynamics of pharmacological treatment: adverse effects are the trial before the prize, so can serve to make the desired effects all the more real. A sub-class of real fictional drugs is fictional drugs with real names. See: beta-phenethylamine (Neuromancer), a powerful of drug apocalyptic hangovers which shares the name of a group of compounds that are the chemical basis for many different psychoactives. So either beta-phenethylamine is a deliberately vague label for something that is chemically much more specific, or William Gibson has just used a bit of licence in its naming20I’m inclined to think the former, on the basis of Gibson’s basically unparalleled capacity for research and synthesis as a sci-fi writer, including in the chemistry of his drugs. I’d love to build a short pharmacopeia as I’ve done in other notes here but an interesting problem with Gibson is that lots of the drugs he uses in his fiction are either already real (‘dex’ in Neuromancer is simply dextroamphetamine) or based on reasoned speculation according to what the chemical elements might actually do. Beta-phenethylamine only makes it into the list – like adrenochrome – because the speculation does not necessarily align with effects. So despite him being one of the godfather’s of cyberpunk, the genre more closely aligned to made-up drugs than any other, it is surprisingly hard to categorise his efforts..

Notes: Obecalp, turning up in a resolutely realist drama like ER21Although ER is not without its sci-fi pedigree, indirectly. It was created by Michael Crichton, who remained an executive producer throughout its run; Crichton also wrote sci-fi theme park thriller Westworld and sci-fi theme park thriller Jurassic Park. Cautionary Tower-of-Babel-ish stories like these have led to Crichton being accused of an anti-science streak, but ER makes an interesting counter-argument, showing repeatedly the miracles of science in the form of medical advancement., is in a way the strangest and most interesting drug in this whole list: it represents a breach of the fictional into the real, in belief itself finding corporality in the folds and fluids of the brain. Whether this evokes the magic of ideas or the mere flesh of it all is up to you.

P is for…

Phenodihydrochloride benzelex

Origin: Withnail and I, a film written and directed by Bruce Robinson (1987).

Appearance: Blue and yellow capsule stored discreetly in the head of a child’s doll.

Alternative street names: The embalmer.

Dose: One.

Effects: Possibly anything.

Adverse effects: Probably everything.

Class: Enigma drugs. These are typically peripheral and mentioned only on occasion, hinting at a deeper and unknown pharmacological stratum to the goings on of the plot. See: DMZ (Infinite Jest), ‘acid that has itself dropped acid’, a hallucinogen possibly derived from mould (that grows on top of another mould) that possibly causes, or treats, a dissociation between thinking and speech, in which a calm thought can be externalised only as screaming; oneirine theophosphate (Gravity’s Rainbow), an intoxicant observed in the clinical setting to induce time-modulation, but recreationally seems to open a chasm of mystical hauntings and theological timeshift hallucinations. Also: drugs with nonsensical names. See: polydichloric euthimal, an amphetamine-ish work drug that miners get addicted to in Outland22It’s also in another Peter Hyams film, The Relic, as a bit of science-looking guff on a computer screen, and in between turned up in Terminator 2: Judgment Day as the chemical explosive used to blow up the Cyberdyne building, which James Cameron included as a nod to his fellow director. I’m aware this is a degree of film trivia you did not need..

Notes: It’s quite possible that Danny the Dope Dealer, purveyor of phenodihydrochloride benzelex but also bullshit artist of the Pollockian mode, simply made the drug up while brandishing some innocuous pill. So maybe it’s fictional even within the film (see black meat).

Q is for…

Quietus

Origin: Children of Men, a film directed by Alfonso Cuarón (2006).

Appearance: Quietus is more broadly the kit that contains a lethal solution and means by which it is self-administered, which appears to be as a drink, hemlock-style.

Effects: Swift and painless death.

Adverse effects: None, assuming death is the aim.

Class: Suicide drugs. Fictionalised suicide drugs are rarer than one might expect, perhaps because one needn’t imagine what adequately exists23Stories that use this tend to focus more on the mechanics than pharmacology, like suicide booths (Futurama) or euthanasia centres (Soylent Green, itself based on Make Room! Make Room!) or, much earlier, the ‘government lethal chamber’ in the Robert Chambers story ‘The Repairer of Reputations’.. Not to be confused with: drugs that induce suicidal ideation as an effect, such as Despair Squid venom (Red Dwarf), which induces hallucinations of situations in which the subject becomes exactly the things they abhor, or botanical neurotoxin (The Happening), which plants produce because they’re evil, or something.

Notes: In the novel from which the film was adapted (by PD James), quietus is not a drug but a government-sanctioned mass drowning. This is considerably creepier than the film’s quietus, which seems banal by comparison, and which is more banal still than the quietus as it appears in the original script, which seems to be a kind of group event where people drink (or are forced to drink, if they have second thoughts) the solution. Having the drownings in the film would have been extremely potent and shocking, but there is something apt about the simple quietus kit, a consumer item delivered like a million boxes sent and received each day. There’s a disarming efficiency to it that’s more plausible – and it has to be plausible, because viewers must be able to imagine themselves choosing the same way out, in the same situation.

R is for…

Repressitol

Origin: The Simpsons episode ‘Bye Bye Nerdie’ (2001).

Appearance: Pills in the time-honoured burnt-orange canister.

Effects: Unspecified repression. Milhouse brandishes his Repressitol when saying happily that he can’t remember his first day of school, presumably because it was too traumatic.

Adverse effects: Milhouse.

Class: Wordplay drugs. See: Fukitol (Robin Williams’s stand-up), the all-encompassing life-noise suppressant; and U4EA (Beverly Hills, 90210), a ’90s club drug conceived for some earnest finger-wagging.

Notes: Over its lifespan The Simpsons has been one of the most prolific synthesisers of fictional drugs24The Simpsons pharmacopoeia

Dimoxinil. Miracle breakthrough in hair-regrowth. Parody of Minoxidil.

Flintstones Chewable Morphine. Kid-friendly opiate. Parody of Flintstones Chewable Vitamins.

Focusyn. Developed to treat attention deficit disorder, Focusyn increases focus, intellectual ability and even politeness. Also paranoia. Parody of Ritalin.

Lithium dibromide. Parody of lithium compounds, sedatives used to treat bipolar and depressive disorders. Could relate to lithium bromide more specifically but that hasn’t been used in treatment since the 1940s. Now it’s used in air conditioning systems.

Moon rocks. Lunar material ground up and freebased, or heated to release its alkaloid from its base. In reality, ‘moon rocks’ has been used to refer to various substances, including synthetic cannabis, a cannabis hash-oil concoction (with its own branding and official mixtapes) and different forms of MDMA. Its use in The Simpsons predates the creation of those I can find histories for, so their names may actually come from the cartoon.

Nappien. Activates the brain’s napping centres and attacks awakegens. Causes sleepwalking. Parody of Ambien.

Stimu-crank. Over-the-counter stimulant used by truck drivers. Works like an amphetamine, therefore, but the ‘crank’ in the name evokes methamphetamine, which would not help with driving a truck at all.

Viagrogaine. Addresses hair loss and erectile dysfunction simultaneously. Side effects include loss of hair and/or penis. Parodic combination of Viagra and Rogaine..

S is for…

Soma

Origin: Brave New World, a novel by Aldous Huxley (1932).

Appearance: Tablets. Or mixed with ice cream.

Dose: “…half a gramme for a half-holiday, a gramme for a week-end, two grammes for a trip to the gorgeous East, three for a dark eternity on the moon…”

Effects: Enhanced sense of well being. Emotional warmth and extroversion. Transcendental insight.

Adverse effects: Eternal enslavement.

Class: Parable drugs. Adds pleasure, removes truth. Also: drugs that were not real and then become real but only in name. Soma is a brand name for carisoprodol, a musculoskeletal relaxant named presumably by someone better at Latin (soma means body) than literature. See: Myostatin (The Incredible Hulk), a fictional drug used in an unremarkable way in an old episode, the name of which was later given to a newly discovered protein related to muscle growth, possibly due to association with the Hulk and his infamous gains.

Notes: An enthusiast for Eastern religion, Huxley likely named soma after the ritual drink of the Vedic traditions, made from a plant extract and believed to be a strong psychedelic.

T is for…

Tripwire 7.0

Origin: Transmetropolitan, a comic by Warren Ellis and Darick Robertson (1997).

Appearance: Pink light in a glass fuse.

Effects: Simulates hallucinations in artificial intelligences.

Adverse effects: Faulty outputs. Scrambled protocols. General fritzing.

Class: Drugs for AIs. See: outrozone (Red Dwarf), a pink liquid used by mechanoids to numb bad memories, risking addiction and damaged circuitry; and electricity (Futurama), regular electrical current jacked into a robot’s head, causing trippy raga montage, addiction and ironic punishment. These are a sub-class of digital drugs. See: snow crash (Snow Crash), a mixed-media techno-theological phenomenon, not strictly a drug or entirely physical, but its digital element is a pixelated pattern that causes the minds of those adept at reading binary to fail like a crashed operating system.

U is for…

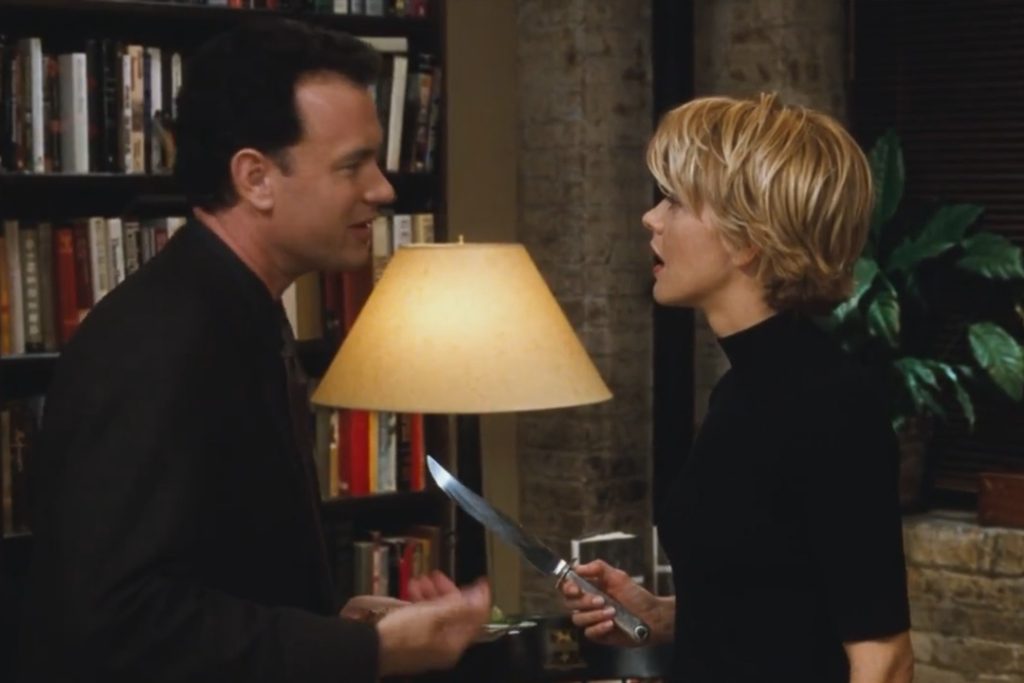

Ultradorm

Origin: You’ve Got Mail, a film directed by Nora Ephron (1998). It’s been clear from the outset that this needs You’ve Got Mail.

Dose: Half a pill before bed.

Effects: Restful sleep.

Adverse effects: A name so contrived as to risk breaking suspension of disbelief (but arguably lots of real drugs have these too).

Class: Hypnotics. If drama is people being conscious and not conscious of things, then the ability to make someone literally unconscious is quite useful to the dramatist. The soporific-to-sedative spectrum of drugs is therefore as much a staple of storytelling as the sleeping potions that preceded them. See: E-Z Doze It Sleeping Pills (Looney Tunes), a cartoon soporific to enable sleep through tornadoes; EZ-4 (Close Encounters of the Third Kind), a knock-out aerosol and possible derivative of the Looney Tunes pill; Hypnocil (A Nightmare on Elm Street 3: Dream Warriors), a sleep drug that suppresses dreams, which is useful if one’s dreams contain Freddy Krueger; and Imobatine (Freddy vs Jason), an intravenous tranquiliser hefty enough fell Jason.

Notes: You’ve Got Mail may seem out of place among the cursed experiments and grubby neon vistas of this list, but non-speculative storytelling is in fact a major market for fictional medications25Although You’ve Got Mail, spiritual successor to Sleepless in Seattle and released in 1998, offers a world in which independent bookshops are ensnared by a technologically advanced corporate entity, devouring them while expanding its web into sectors beyond. So it may be the most prophetically dystopian work on this list.. Often this is for copyright reasons: drug names are invented to avoid unwanted commercial implications with manufacturers of real-world originals, allowing the drugs to alleviate headaches of characters and producers alike.

V is for…

Vurt feathers

Origin: Vurt, a novel by Jeff Noon (1993). Beyond that very little is clear.

Appearance: Avian plumage in assorted colours.

Dose: A feather inserted into the mouth.

Effects: Vurt feathers will admit the user to one of a series of shared ‘vurt worlds’, in which they have experiences alongside other users. The vurts are characterised by the colour of their feather, with tamer ones running like television shows and even having advertisements, while others are stranger and more dangerous. Users can ‘jerk out’ of a vurt by physically jolting themselves (perhaps taken from lucid dreaming, which is probably a nearer analogue to the vurt than actual drug-taking).

Adverse effects: Beyond the run-of-the-mill downers found in various vurts, if you die in the yellow vurt then you die in real life26See: A Nightmare on Elm Street, where if you die in a dream then you die in real life; and Bojack Horseman, where if you die in improv comedy then you die in real life.. It also appears that people can be transported bodily into or out of the vurt, which is odd.

Class: Shared-reality drugs. See: Can-D and Chew-Z (The Three Stigmata of Palmer Eldritch), note 19.

Notes: Published in 1993 and set in Manchester, Vurt is a mad-for-it Britpop cyberpunk that reads like Shaun Ryder trying to recall Neuromancer verbatim and accidentally making up a new novel. It is mostly incomprehensible. Likely this is because it reflects performatively how its drug-subject feels through the way it reads. As mythopharmacologists we must consider this stylistically honourable, even if we are short-changed on specifics.

W is for…

Water of Lethe

Origin: Greek mythology. A river flowing from a cave (or perhaps only through it) in the underworld (or perhaps the island of Lemnos)27As with all mythology there is no official lore; there are various sources and often variations between them, especially in geography. But the Lethe does in one way or another snake through them all. The word means ‘forgetfulness’ or ‘oblivion’ and is the origin of ‘lethargic’ and ‘lethal’..

Appearance: Standard H2O.

Dose: A draft cupped from the river

Effects: Erasure of memory. Used by the souls of the dead to forget their previous lives ahead of reincarnation. This was believed mostly by the Orphist mystical movement, but was compelling enough to wend its way into wider myth.

Adverse effects: None. Does the job.

Class: Life-suppressants. Some tellings of the River Lethe have the mouth of its origin-cave speckled with poppies, which were used even in classical times to produce opium for anaesthetic (when ether was first used as an anaesthetic it was referred to by some as ‘letheron’) and recreation. The myth of the water of oblivion equally has this superficially functional but secretly attractive quality: its lure for some is not only in the possibility of ‘restarting’ life but in the period between drinking and waking renewed: in nothingness itself. In literature it’s therefore often portrayed as something one strays into and is forever lost28Even though this is at odds with what is known of the ceremonial Orphist use. Opium (taken as a drink) could well be the origin of the tradition among Orphists, who could – one might speculate – have used it ritualistically.. See: nepenthe (Greek mythology), another drug to induce forgetfulness but more specifically for the elimination of sorrow; and Prozium (Equilibrium), extinguisher of emotion and facilitator of dystopia in the line of Brave New World and We, but with gun fu.

Notes: Being an element of classical mythology means the Lethe is referenced in a great many literary places, but for the same reason many of its references seem perfunctory: in the centuries leading to the twentieth, the classics were a pillar of every wealthy western man’s education, making their gods and stories a kind of vocabulary for expressing current surroundings as if to draw insightfully on some wider cosmogony of thought. But for most, including even very good writers, this was just a way to signal one’s education through easy simile. Or at least that’s my view through the lens of a different time. Perhaps future generations will do it with the Marvel Cinematic Universe – which of course takes any number of themes and references from the Greek Mythological Universe29The second highest grossing Marvel film to date is Avengers: Infinity War, antagonist of which is Thanos, whose name comes from Thanatos, god of death and twin brother to Hypnos, god of sleep, from whose cave the Lethe flows., as collaboratively made fictions often do, and itself likely takes the same from preceding pagan and animist story systems going back to whatever cave that spouted it all.

X is for…

X-cell

Origin: Fallout 4, from the long-running post apocalyptic role-playing game series (2015).

Appearance: Inhaler with twin canisters. In keeping with the logic of games, its rarity is proportional to its power.

Dose: One click.

Effects: Gives a boost to every one of your stats for a short period.

Adverse effects: If you become addicted, some of your stats will be diminished until you take more.

Class: Power-up drugs. You may have noticed that you don’t have ‘stats’ but rather a complex and confusing bundle of cells you call a body. But modelling this body as various characteristics and then bumping these up or down is a convenient a way of integrating drug-use with gameplay mechanics. The give-and-take of drug narrative is here envisaged more clearly than in any film: as player you feel performance benefits and then withdrawal disbenefits. Fallout is prodigious in its use of what it calls ‘chems’, including: psycho30Possibly from Brian Aldis’s Barefoot in the Head, in which ‘Psycho-Chemical Aerosols’ are released over Europe to send its populations into psychedelic terror and joy., which makes you stronger; mentats31Possibly from the mentats in Dune, the human thought-machines that have come to replace computers in the series., which make you smarter (see hormone K) and the stim-pack, the ubiquitous game convention that increases your health. See: 1-up mushroom (Super Mario), the restorative fungi that Mario chomps throughout and which have no disbenefits per se, unless Super Mario is read as one Italian plumber’s magic mushroom trip from which he can never escape, locked in a delusional cycle that tells him the only way out is to eat the hallucinogenic 1-ups, which only push him further in. In this reading the ‘mega star’ would probably be amphetamines (a futile attempt to level himself out), the ‘fire flower’ cocaine and the ‘cape feather’ some kind of prescription anxiolytic, maybe diazepam, given the game’s era.

Y is for…

Ygramul’s poison

Origin: The Neverending Story, a novel by Michael Ende. It’s the venom of what is seemingly a hellish cave-dwelling spider, but which is actually a hellish shapeshifting cloud of cerebrally linked insects. (The spider/insects – Ygramul the Many – is/are sadly not in the 1984 film adaptation.)

Effects: Ability to teleport anywhere just by thinking of it.

Adverse effects: Death in one hour.

Class: Imagination drugs. It would be easy to think this combination of effects as so disparate and nakedly story-serving as to be quite lazy, from the mythopharmacologist’s point of view. But the setting of all this, Fantastica, is actually a realm of pure imagination that lives secretly in all real-world minds as a sort of underlying shared hallucination, and in this context Ygramul’s poison is not a drug but is itself the effect of the real drug, which is The Power of Imagination. This is heartwarming stuff until you get eaten by a hellish mind-spider.

Notes: While The Neverending Story offers no biological or chemical explanation of Ygramul the Many’s hunting mechanism, to avoid accidentally teleporting all over the place herself, the poison could be created only at the point of its injection into prey through a combining of two previously separate chemicals. The real-world bombardier beetle produces a corrosive acidic spray through mixing two separate chemicals that would – if combined internally – cause it to explode, or at least melt. This has led entomologically inclined creationists to claim it an example ‘irreducible complexity’, or something that could not have developed by the successive mutation of evolution and therefore proof of intelligent design. It is unclear if creationists of Fantastica use Ygramul in the same way. But given that Fantastica is generated through our collective imagination, the creationist worldview would be an objective reality of one of its levels. This all is perhaps less digressive than it appears: Ende was influenced by the German movement of anthroposophy, which holds the spiritual world to have a separate but concrete reality that can be examined no less scientifically than our own. The Neverending Story seems a direct expression of this idea.

Z is for…

Zyme

Origin: Deus Ex, Warren Spector’s influential game (2000). And yet also unknown, made in the basement labs of New York City as it’s gripped by crime and a mysterious nanotech virus sweeps America. Blame the Illuminati.

Appearance: Crystals in a vial that would likely have been conical if there were enough polygons to go around at the time.

Effects: General euphoria. Reduced inhibitions, if that’s your thing.

Adverse effects: Confused motor function. Visual impairment. Moreish.

Class: Crimewave drugs. Effects vague yet consumingly powerful, they turn people into crazed criminals who will do anything to get more32Many emerged as an echo of the crack cocaine epidemic of 1980s America, in which city communities met an influx of the cheaply made and highly addictive drug, the associated criminality and reactionary policing that made some areas feel (at least according to the press, whose caricatures of the event are what these fictional versions really draw from) like warzones.. Used in stories chiefly to enable societal breakdown; their actual effects are somewhat boring, being extreme but also very simple. See: spank (Grand Theft Auto III), a powdered street drug that makes people want to engage in crime, any crime, and sometimes blow themselves up; nuke (Robocop 2), a bright red solution that makes people want to wear leather jackets and shoot uzis ineffectually at cyborgs; and – long preceding the crack-cocaine origins of the previous, and granddaddy of ultraviolence-drugs – moloko plus33‘Moloko’ means ‘milk’ and comes from Russian, along with much of the novel’s invented slang, while the ‘plus’ is stated to be a mixture of synthmesc (presumably ‘synthetic mescaline’), vellocet (presumably a sort of speed, as in ‘velocity’), and drencrom (presumably from adrenochrome, Anthony Burgess having perhaps heard the same things about it as Hunter S Thompson – see adrenochome). (A Clockwork Orange), a milk-based cocktail that fuels a night’s in-out with one’s droogs. Stanley Kubrick’s film adaptation of A Clockwork Orange was banned for a time, becoming a sort of avant-garde video nasty, and across these examples we can observe some chemical similarity with moral panic drugs (see made-up drugs under cake).

Directions for use

While it may be tempting to claim that fictional drugs operate foremost as social commentary, the line between detached analysis and vicarious pleasure is blurred in any fiction, no matter how high-minded it claims to be. Fictional drugs, in particular those that offer not just the means to a narrative end but an experience, are a condensing of this blurred vicarious zone.

These are the ones we need more of. Not just for the horrors, the hallucinated bats swooping at Hunter S Thompson over the highways of Nevada, but more simply for the feelings we are told exist but have not ourselves experienced, whether because we have not thought to do so, or had the opportunity, or because in reality it would be a terrible idea.

These are the primal fear, the sensual glory (frequently sordid – which is key) and most importantly they are the confusion of the new – the most productive state there is. Fictional drugs, in other words, do what stories do. They are the trip within a trip.

Notes